...it’s Facebook’s official opinion that you’ve 'negated' your claim to any privacy whatsoever..."

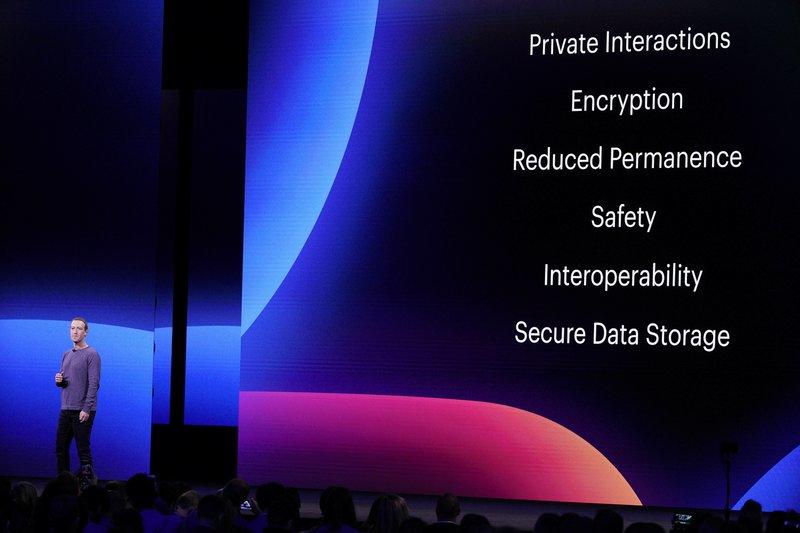

Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg recently rolled out with a new mantra: "The future is private."

Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg recently rolled out with a new mantra: "The future is private." By Tyler Durden: A new report by The Intercept has unearthed some stunning quotes from Facebook's lawyers as the controversial social media giant recently battled litigation in California courts related to the Cambridge Analytica data sharing scandal. The report notes that statements from Facebook's counsel "reveal one of the most stunning examples of corporate doublespeak certainly in Facebook’s history" concerning privacy and individual users' rights.

Contrary to CEO Mark Zuckerberg's last testimony before Congress which included the vague promise, “We believe that everyone around the world deserves good privacy controls,” the latest courtroom statements expose in shockingly unambiguous terms that Facebook actually sees privacy as legally "nonexistent"

— to use The Intercept's apt description of what's in the courtroom transcript — up until now largely ignored in media commentary.

The courtroom debate was first reported by Law360, and captures the transcribed back and forth between Facebook lawyer Orin Snyder of Gibson Dunn & Crutcher and US District Judge Vince Chhabria.

The Intercept cites multiple key sections of the transcript from the May 29, 2019 court proceedings showing Snyder arguing essentially something the complete opposite of Zuckerberg's public statements on data privacy, specifically, on the idea that users have any reasonable expectation of privacy at all.Facebook's lawyer argued:

There is no privacy interest, because by sharing with a hundred friends on a social media platform, which is an affirmative social act to publish, to disclose, to share ostensibly private information with a hundred people, you have just, under centuries of common law, under the judgment of Congress, under the SCA, negated any reasonable expectation of privacy.As The Intercept commented of the blunt remarks, "So not only is it Facebook’s legal position that you’re not entitled to any expectation of privacy, but it’s your fault that the expectation went poof the moment you started using the site (or at least once you connected with 100 Facebook “friends”)."

Judge Chhabria took issue with the "binary" nature of Facebook's conception of privacy in stating, “like either you have a full expectation of privacy, or you have no expectation of privacy at all,” and put the following scenario to Facebook's legal team:

If I share [information] with ten people, that doesn’t eliminate my expectation of privacy. It might diminish it, but it doesn’t eliminate it. And if I share something with ten people on the understanding that the entity that is helping me share it will not further disseminate it to a thousand companies, I don’t understand why I don’t have — why that’s not a violation of my expectation of privacy.Snyder's response was illuminating regarding Facebook's approach to users' privacy:

Let me give you a hypothetical of my own. I go into a classroom and invite a hundred friends. This courtroom. I invite a hundred friends, I rent out the courtroom, and I have a party. And I disclose — And I disclose something private about myself to a hundred people, friends and colleagues. Those friends then rent out a 100,000-person arena, and they rebroadcast those to 100,000 people. I have no cause of action because by going to a hundred people and saying my private truths, I have negated any reasonable expectation of privacy, because the case law is clear.And more from The Intercept's commentary, which concluded: "Using Facebook is a depressing party taking place in a courtroom, for some reason, that’s being simultaneously broadcasted to a 100,000-person arena on a sort of time delay. If you show up at the party, don’t be mad when your photo winds up on the Jumbotron. That is literally the company’s legal position."

Repeatedly, Snyder blamed the users for their own surveillance throughout the metaphors and hypothetical situations presented:

This is why every parent says to their child, “Do not post it on Facebook if you don’t want to read about it tomorrow morning in the school newspaper,” or, as I tell my young associates if I were going to be giving them an orientation, “Do not put anything on social media that you don’t want to read in the Law Journal in the morning.” There is no expectation of privacy when you go on a social media platform, the purpose of which, when you are set to friends, is to share and communicate things with a large group of people, a hundred people.And a another key question from what appeared an incredulous Judge Chhabria: “If Facebook promises not to disseminate anything that you send to your hundred friends, and Facebook breaks that promise and disseminates your photographs to a thousand corporations, that would not be a serious privacy invasion?"

Reflecting a viewpoint that Facebook considers almost no scenario at all a potential "privacy invasion," Snyder responded:

“Facebook does not consider that to be actionable, as a matter of law under California law.”Thus Facebook admitted in court that even when the company gives a user the impression it will not share private information which that user has not authorized for public view, should the platform violate this, it is still not illegal nor does it violate Facebook's own standards.

“If you really want to be private,” Facebook's counsel said to the court, “there are people who have archival Facebook pages that are like their own private mausoleum. It’s only set to [be visible by] me, and it’s for the purpose of repository, you know, of your private information, and no one will ever see that.”

Essentially the argument conceded that in Facebook's eyes sharing something with two friends by default authorizes the company to share it with 20, or 200, or 200,000 — or as The Intercept points out: "it’s Facebook’s official opinion that you’ve 'negated' your claim to any privacy whatsoever - from the moment you login to the site.

Read The Intercept's full damning report here, and access the full transcript of the courtroom proceedings here.

Source

No comments:

Post a Comment