Lt. Col. Karen Kwiatkowski was an eye-witness to the tactics employed by Jews in the Pentagon by which disinformation was manufactured and fed to the White House, Congress, media, and American public that led to the Iraq war.

The Iraq War has cost the U.S. $2 trillon dollars, and the lives of approximately 6,000 Americans and 200,000 Iraqi civilians (multitudes

more are permanently disabled)… The war also led to the rise of ISIS

and the destabilization throughout the Middle East that has impacted

others around the world…

The articles below are reposted from American Conservative, Salon, and Antiwar.com, 2003-2004.

Photos have been added by IAK. For additional info on the individuals’ connections to Israel see this.

(Related videos are below post.)

American Conservative

By Lt. Col. Karen Kwiatkowski (USAF-ret), Dec 2003-Jan 2004 (3-part series)

In early May 2002, I was looking forward to retirement from the United States Air Force in about a year. I had a cushy job in the Pentagon’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, International Security Affairs, Sub-Saharan Africa.

In the previous two years, I had published two books on African security issues and had passed my comprehensive doctoral exams at Catholic University. I was very pleased with the administration’s Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Sub-Saharan Africa, former Marine and Senator Helms staffer Michael Westphal, and was ready to start thinking about my dissertation and my life after the military.

When Mike called me in to his office, I thought I was getting a new project or perhaps that one of my many suggestions of fun things to do with Africa policy had been accepted. But the look on his face clued me in that this was going to be one of those meetings where somebody wasn’t leaving happy. After a quick rank check, I had a good idea which one it would be.

There was a position in Near East South Asia (NESA) that they needed to fill right away. I wasn’t interested. They phrased the question another way: “We have been tasked to send a body over to Bill Luti. Can we send you?” I resisted—until I slowly guessed that in true bureaucratic fashion and can-do military tradition my name had already been sent over. This little soirée in Mike’s office was my farewell.

“Write down everything you see.”

I went back to my office and e-mailed a buddy in the Joint Staff. Bob wrote back, “Write down everything you see.” I didn’t do it, but these most wise words from a trusted friend proved the first of three omens I would soon receive.

I showed up down the hall a few days later. It looked just like the office from which I came, newer blue cubicles, narrow hallways piled high with copy paper, newspapers, unused equipment, and precariously leaning map rolls. The same old concrete-building smell pervaded, maybe a little mustier. I was taking over the desk of a CIA loaner officer. Joe had been called back early to the agency and was hoping to go to Yemen. Before he left, he briefed me on his biggest project: ongoing negotiations with the Qatari sheiks over who was paying for improvements to Al Udeid Air Base. I was familiar with Al Udeid from my time on the Air Staff a few years before. Back then we seemed to like the Saudis, and our Saudi bases were a few hours closer to the action than Al Udeid, so the U.S. played a woo-me game. Now that we needed and wanted Al Udeid to be finished quickly and done up right, it was time for the emirs to play hard to get. Joe gave me the rundown on counterterrorism ops in Yemen and an upcoming agreement with the Bahraini monarch to extend our military-security agreement, locking in a relationship just in case those Bahraini experiments with democracy actually took off.

I had an obligatory meeting with the deputy director, Paul Hulley, Navy Captain. This meeting followed a phone call in which I hadn’t been as compliant as I should have been with a Navy Captain, and since Paul had handled my bad attitude with candor and grace, I was determined to like him—and I did. I gave him my story: I was a year from retirement and, more importantly, I was in a car pool. I’d be working a 7:15 to 17:30 schedule. He was neither charmed nor impressed. He advised that I’d need to be working a lot longer than that.

Then we stepped in to meet Deputy Undersecretary of Defense Bill Luti. I knew Luti had a Ph.D. in international relations from the Fletcher School at Tufts and was a recently retired Navy Captain himself. At this point, I didn’t know what a neocon was or that they had already swarmed over the Pentagon, populating various hives of policy and planning like African hybrids, with the same kind of sting reflex. Luti just seemed happy to have me there as a warm body. [Luti had been recruited by Albert Wohlstetter, known as the “neocons’ guru”.]

‘Don’t say anything positive about Palestinians’

My second omen was the super-size bottles of Tums and Tylenol Joe left in his desk. The third occurred as I was chatting with my new office mate, a career civil servant working the Egypt desk. As the conversation moved into Middle East news and politics, she mentioned that if I wanted to be successful here, I shouldn’t say anything positive about the Palestinians. In 19 years of military service, I had never heard such a politically laden warning on such an obscure topic to such an inconsequential player. I had the sense of a single click, the sound tectonic plates might make as they shift deep under the earth and lock into a new resting position—or when the trigger is pulled in a game of Russian roulette.

Key personnel are replaced

I had never worked for neocons before, and the philosophical journey to understand what they stood for was not a trip I wanted to take. But my conversations with coworkers and some of the people I was meeting in the office opened my eyes to something strange and fascinating. Those who had watched the transition from Clintonista to Bushite knew that something calculated had happened to NESA. Key personnel, long-time civilian professionals holding the important billets, had been replaced early in the transition. The Office Director, second in command and normally a professional civilian regional expert, was vacant. Joe McMillan had been moved to the NESA Center over at National Defense University. This was strange because in a transition the whole reason for the Office Director being a permanent civilian (occasionally military) professional is to help bring the new appointee up to speed, ensure office continuity, and act as a resource relating to regional histories and policies. To remove that continuity factor seemed contraindicated, but at the time, I didn’t realize that the expertise on Middle East policy was being brought in from a variety of outside think tanks.

Another civilian replacement about which I was told was that of the long-time Israel/Syria/Lebanon desk, Larry Hanauer. Word was that he was even-handed with Israel, there had been complaints from one of his countries, and as a gesture of good will, David Schenker, fresh from the Washington Institute, was serving as the new Israel/Syria/Lebanon desk. [The Washington Institute for Near East Affairs is an Israel advocacy organization.]

I came to share with many NESA colleagues a kind of unease, a sense that something was awry. What seemed out of place was the strong and open pro-Israel and anti-Arab orientation in an ostensibly apolitical policy-generation staff within the Pentagon. There was a sense that politics like these might play better at the State Department or the National Security Council, not the Pentagon, where we considered ourselves objective and hard boiled.

The anti-Arab orientation I perceived was only partially confirmed by things I saw. Towards the end of the summer, we welcomed to the office as a temporary special assistant to Bill Luti an Egyptian-American naval officer, Lt. (later Lt. Cmdr.) Youssef Aboul-Enein. His job wasn’t entirely clear to me, but he would research bits of data in which Bill Luti was interested and peruse Arabic-language media for quotations or events that could be used to demonize Saddam Hussein or link him to nastiness beyond his own borders and with unsavory characters.

While I was still hoping to be sent back to the Africa desk, I was also angling to take the NESA North Africa desk that would be vacated in July. During this time, May through mid-July, the news in the daily briefing was focused on war planning for the Iraq invasion. Slides from a CENTCOM brief appeared on the front page of the New York Times on July 5. A few weeks later, Secretary Donald Rumsfeld ordered an investigation into who leaked this information. The Air Force Office of Special Investigation was tasked to work with the FBI, and everyone in NESA was supposed to be interviewed.

My interview, by two fresh-faced OSI investigators, occurred sometime in July. One handed me a copy of an article by William Arkin discussing Iraq-war planning published in May 2002 in the Los Angeles Times and asked if I knew Arkin. I didn’t recall the name, but when I checked I learned that he had spent time at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS). Apparently, Arkin had facilitated a leak six weeks before, but it hadn’t caused a fuss. I pointed out that I did know a person with major SAIS links who probably knew Arkin. They leaned forward eagerly. “Have you ever heard of Paul Wolfowitz?” They looked puzzled, so I called up the bio of the deputy secretary and showed them how he ran SAIS during most of the Clinton years. I suggested the investigation look at the answers to the cui bono question. I also told them no one in the military or at CENTCOM would leak war plans because as Rumsfeld accurately said, it gets people killed. But the politicos who were anxious to get the American people over the mental hump that the Bush administration was going to send troops to Iraq were not military and had both motive and opportunity to leak.

During the summer, I assumed the duties of the North Africa desk. Part of my job was to schedule and complete two overdue bilateral meetings with longtime U.S. security partners Morocco and Tunisia. Bilateral meetings historically included a tailored regional-security briefing addressing Weapons of Mass Destruction threats and status. In planning my upcoming bilateral agendas and attendee lists, I discovered that Bill Luti had certain issues regarding the regional-security briefing, in particular with the aspects relating to WMD and terrorism.

There had been an incident shortly before I arrived in which the Defense Intelligence Officer had been prohibited from giving his briefing to a particular country only hours before he was scheduled. During the summer, the brief was simply not scheduled for another important bilateral meeting. Instead, a briefing was prepared by another policy office that worked on non-proliferation issues. This briefing was not a product of the Defense Intelligence Agency or CIA but instead came from the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

Office of Special Plans secretly produces talking points

At the end of the summer of 2002, new space had been found upstairs on the fifth floor for an “expanded Iraq desk.” It would be called the Office of Special Plans. We were instructed at a staff meeting that this office was not to be discussed or explained, and if people in the Joint Staff, among others, asked, we were to offer no comment. We were also told that one of the products of this office would be talking points that all desk officers would use verbatim in the preparation of their background documents.

About that same time, my education on the history and generation of the neoconservative movement had completed its first stage. I now understood that neoconservatism was both unhistorical and based on the organizing construct of “permanent revolution.” I had studied the role played by hawkish former Sen. Scoop Jackson (D-Wash.) and the neoconservative drift of formerly traditional magazines like National Review and think tanks like the Heritage Foundation. I had observed that many of the neoconservatives in the Pentagon not only had limited military experience, if any at all, but they also advocated theories of war that struck me as rejections of classical liberalism, natural law, and constitutional strictures. More than that, the pressure of the intelligence community to conform, the rejection of it when it failed to produce intelligence suitable for supporting the “Iraq is an imminent threat to the United States” agenda, and the amazing things I was hearing in both Bush and Cheney speeches told me that not only do neoconservatives hold a theory based on ideas not embraced by the American mainstream, but they also have a collective contempt for fact.

By August, I was morally and intellectually frustrated by my powerlessness against what increasingly appeared to be a philosophical hijacking of the Pentagon. Indeed, I had sworn an oath to uphold and defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic, but perhaps we were never really expected to take it all that seriously.

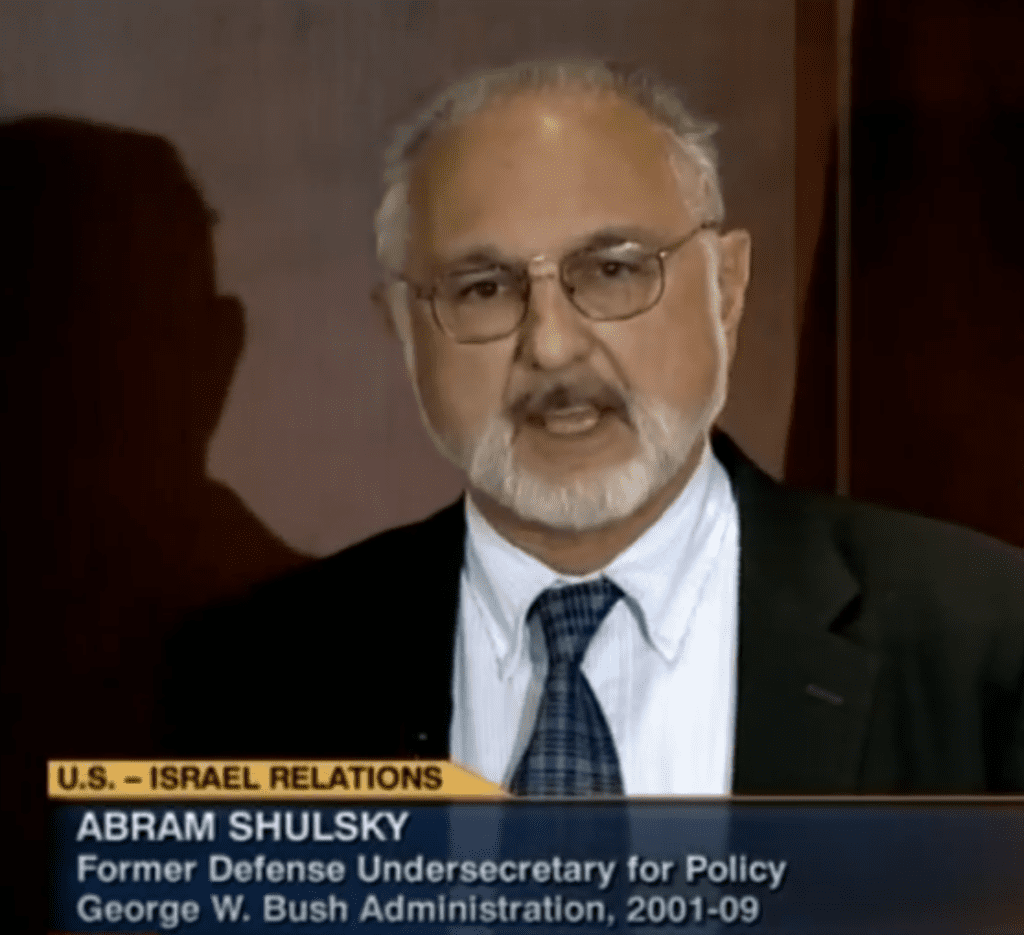

(Part 2) By the end of the summer of 2002, our Near East South Asia (NESA) office spaces were beginning to get crowded. Several senior people, including Abe Shulsky had moved into some of the enclosed front offices, and the cubicles were entirely filled, as were some less than ideal workspaces in the hallway.

Chatter swirled, and word went out that NESA was looking for additional space. By late August, a large office was located upstairs on the fifth floor. At a staff meeting, we were told that the expanded Iraq desk would become the Office of Special Plans and would move out. We were told not to refer to this office as the Office of Special Plans and, if pressed, we were also not to confirm that it was the expanded Iraq desk. This instruction came across as both surreal and humorous. When someone asked whether we could tell our Joint Staff counterparts, Bill Luti said no, to deny knowledge of the organizational shift. In my experience, our canny, connected, and cynical Joint Staff counterparts probably already knew more about it than we did, and this suspicion was later confirmed in conversations with some of them.

The subterfuge was not necessary in any case, as several weeks later Luti was announced as the new Deputy Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, NESA and Special Plans, allowing him to work directly for Undersecretary Doug Feith. Luti had always seemed to work directly for Feith. In one staff meeting, interrupted by a call from Feith’s office, Luti, in his famously incautious manner, proclaimed to all present, that Feith couldn’t wipe his ass without his [Luti’s] help.

The establishment of the Office of Special Plans, under Abe Shulsky, and including several military folks, a civil servant or two, and the larger group of neocon-friendly appointees or contractors, meant to the rest of us that we would have more space and a reduction in cross-regional chatter. The Iraq-war planning aspect would now be isolated from the rest of NESA and would establish its own rhythm and cadence, separate from the non-political-minded professionals covering the rest of the region. In planning a war, loose lips sink ships, and if anyone didn’t remember this World War II slogan, the Pentagon had several posters in common areas to remind us. (Interestingly, the planning and execution of wars—writing and implementing war plans—is the function of the Combatant Commander, with the Joint Staff as chief technical advisor and the Undersecretary of Policy as policy advisor. The Secretary of Defense approves, but combatant commanders work directly for the president. Nowhere in OSD should one, by law, custom, or common sense, find people busy developing and writing war plans, even if they are special.)

If they were not writing war plans, the Office of Special Plans did produce something related to the upcoming war. By August, only the Pollyannas at the Pentagon felt that the decision to invade Iraq, storm Baghdad, and take over the place (or give it to Ahmad Chalabi) was reversible. What was still being worked out at that time was the propaganda piece, a sustained refinement of the storyline that had been hinted at in neoconservative circles and the White House for months, even years. Based on the successful second leak of the war plans in July, Washington’s initial reactions of “Oh, no—so many troops!” was shaped masterfully by the Pentagon publicity machine with offended and vociferous denials of the stories, claiming that the operation would not require nearly that many troops. It was a propaganda coup of understated elegance and razor-edged acumen.

That genius, in some ways, was due to Abe Shulsky. A kindly and gentle-appearing man who would say hello in the hallways, he seemed to be someone with whom I, as a political-science grad student, would have loved to sit over coffee and discuss the world’s problems. Seeing me as a uniformed and relatively junior officer, I doubt he entertained similar desires. In any case, he was very busy. I didn’t see much of what Abe did on a daily basis, but I know that he approved a particular document produced by the Office of Special Plans for the staff officers in Policy. Desk officers write policy papers for our senior officers to help prepare them for meetings, speeches, or events where they will need to communicate U.S. security policy. In early September, after the OSP had been established, we were told via staff meetings and e-mails that whenever we wrote something that might include reference to the Iraq threat, and WMD and terrorism in general, we would now inform OSP and request their talking points. The actual contact point was Air Force Col. Kevin Jones. On a number of occasions from September through January, I e-mailed or called Colonel Jones and requested the latest version of the talking points. On several occasions, they weren’t available in an approved form, and we waited for Shulsky’s OK. This crafting and approval of the exact words to use when discussing Iraq, WMD, and terrorism were, for most of us, the only known functions of OSP and Mr. Shulsky.

As a desk officer, having a patented set of words to copy meant less to research, and I welcomed the talking points on principle. Then I made the mistake of reading them. They were a series of bulletized statements, written in a convincing way, and at first glance, they seemed reasonable and rational. Up to a point. Saddam Hussein had gassed his neighbors, abused his people, and was continuing in that mode, a threat to his neighbors and to us. Saddam Hussein tried to shoot at our aircraft when they enforced the no-fly zone. Saddam Hussein had harbored al-Qaeda operatives and offered and probably provided them training facilities. Saddam Hussein was pursuing and had WMD of the type that could be used by him, in conjunction with al-Qaeda and other terrorists, to attack and damage American interests, Americans, and America. Saddam Hussein had not been seriously weakened by war and sanctions and weekly bombings over the past 12 years and in fact was plotting to hurt America and support anti-American activities, in part through terrorists. His support for the Palestinians and Arafat proved his terrorist connections, and, basically, the time to act was now. This was the gist of the talking points, and they remained on message throughout the time I watched them evolve.

But evolve they did, and the subtle changes I saw from September to late January were revealing as to what exactly the Office of Special Plans was contributing to national security. Two key types of modifications would be directed, or approved, by Abe Shulsky and his team of politicos. First was the deletion of entire references or bullets. The one I remember most specifically is when they dropped the bullet that said one of Saddam’s intelligence operatives met with Mohamed Atta in Prague and that this was salient proof that Saddam was in part responsible for the 9/11 attack. It lasted through several revisions, but after the media reported the claim as unsubstantiated by U.S. intelligence, denied by the Czech government, and that the location of Atta had been confirmed to be elsewhere by our own FBI, that particular bullet was dropped entirely from our “advice on things to say” to senior Pentagon officials when they met with guests or outsiders.

The other type of change to the talking points was along the lines of fine-tuning and generalizing. Much of what was there was already so general as to be less than accurate. Some bullets would be softened, particularly statements of Saddam’s readiness and capability in the chemical, biological, or nuclear arena. Others were altered over time to match more exactly something Bush or Cheney had said in recent speeches. One item I never saw in our talking points was a reference to Saddam’s purported attempt to buy yellowcake uranium in Niger. The OSP list of crime and evil included a statement relating to Saddam’s attempts to seek fissionable materials or uranium in Africa. (Our point, written mostly in the present tense had conveniently omitted dates of the last known attempt, some time in the late 1980s.) I was later surprised to hear the president’s mention of the yellowcake in Niger because that indeed would be new, and in theory might have represented new actual intelligence, something remarkably absent in what we were seeing from the OSP.

During the late summer and fall I was industriously trying to get our overdue bilateral visits with Morocco and Tunisia back on schedule. There must have been clues throughout the fall that I was less than politically reliable. On the wall behind my desk, I had a display of cartoons and articles questioning the legality and justness of pre-emptive wars, images of neoconservatives gone wild, and other antiwar humor. I had plenty of visitors, and even folks who I had pegged as a little too imperialist for my taste enjoyed my personal wailing wall. But as winter approached, the propaganda campaign gained ground, Congress bought in, my sense of humor darkened, and the cartoons selected for the wall got angrier. It was becoming clearer that, after a year, the Afghan campaign was not proceeding as promised, and Iraq having been falsely advertised and politically manipulated would be even uglier and deadlier. And no one in the Pentagon with any political or moral power seemed to care.

(Part 3) As the winter of 2002 approached, I was increasingly amazed at the success of the propaganda campaign being waged by President Bush, Vice President Cheney, and neoconservative mouthpieces at the Washington Times and Wall Street Journal. I speculated about the necessity but unlikelihood of a Phil-Dick-style minority report on the grandiose Feith-Wolfowitz-Rumsfeld-Cheney vision of some future Middle East where peace, love, and democracy are brought about by pre-emptive war and military occupation.

In December, I requested an acceleration of my retirement after just over 20 years on duty and exactly the required three years of time-in-grade as a lieutenant colonel. I felt fortunate not to have being fired or court-martialed due to my politically incorrect ways in the previous two years as a real conservative in a neoconservative Office of Secretary of Defense. But in fact, my outspokenness was probably never noticed because civilian professionals and military officers were largely invisible. We were easily replaceable and dispensable, not part of the team brought in from the American Enterprise Institute, the Center for Security Policy, and the Washington Institute for Near East Affairs.

There were exceptions. When military officers conspicuously crossed the neoconservative party line, the results were predictable—get back in line or get out. One friend, an Army colonel who exemplified the qualities carved in stone at West Point, refused to maneuver into a small neoconservative box, and he was moved into another position, where truth-telling would be viewed as an asset instead of a handicap. Among the civilians, I observed the stereotypical perspective that this too would pass, with policy analysts apparently willing to wait out the neocon phase.

Israeli generals visit the Pentagon – don’t sign in

In early winter, an incident occurred that was seared into my memory. A coworker and I were suddenly directed to go down to the Mall entrance to pick up some Israeli generals. Post-9/11 rules required one escort for every three visitors, and there were six or seven of them waiting. The Navy lieutenant commander and I hustled down. Before we could apologize for the delay, the leader of the pack surged ahead, his colleagues in close formation, leaving us to double-time behind the group as they sped to Undersecretary Feith’s office on the fourth floor. Two thoughts crossed our minds: are we following close enough to get credit for escorting them, and do they really know where they are going? We did get credit, and they did know. Once in Feith’s waiting room, the leader continued at speed to Feith’s closed door. An alert secretary saw this coming and had leapt from her desk to block the door. “Mr. Feith has a visitor. It will only be a few more minutes.” The leader craned his neck to look around the secretary’s head as he demanded, “Who is in there with him?”

This minor crisis of curiosity past, I noticed the security sign-in roster. Our habit, up until a few weeks before this incident, was not to sign in senior visitors like ambassadors. But about once a year, the security inspectors send out a warning letter that they were coming to inspect records. As a result, sign-in rosters were laid out, visible and used. I knew this because in the previous two weeks I watched this explanation being awkwardly presented to several North African ambassadors as they signed in for the first time and wondered why and why now. Given all this and seeing the sign-in roster, I asked the secretary, “Do you want these guys to sign in?” She raised her hands, both palms toward me, and waved frantically as she shook her head. “No, no, no, it is not necessary, not at all.” Her body language told me I had committed a faux pas for even asking the question. My fellow escort and I chatted on the way back to our office about how the generals knew where they were going (most foreign visitors to the five-sided asylum don’t) and how the generals didn’t have to sign in. I felt a bit dirtied by the whole thing and couldn’t stop comparing that experience to the grace and gentility of the Moroccan, Tunisian, and Algerian ambassadors with whom I worked.

Kristol, Krauthammer, Abrams vs Zinni, Powell, Scowcroft

In my study of the neoconservatives, it was easy to find out whom in Washington they liked and whom they didn’t. They liked most of the Heritage Foundation and all of the American Enterprise Institute. They liked writers Charles Krauthammer and Bill Kristol. To find out whom they didn’t like, no research was required. All I had to do was walk the corridors and attend staff meetings. There were several shared prerequisites to get on the Neoconservative List of Major Despicable People, and in spite of the rhetoric hurled against these enemies of the state, most really weren’t Rodents of Unusual Size. Most, in fact, were retired from a branch of the military with a star or two or four on their shoulders. All could and did rationally argue the many illogical points in the neoconservative strategy of offensive democracy—guys like Brent Scowcroft, Barry McCaffrey, Anthony Zinni, and Colin Powell.

I was present at a staff meeting when Deputy Undersecretary Bill Luti called General Zinni a traitor. At another time, I discussed with a political appointee the service being rendered by Colin Powell in the early winter and was told the best service he could offer would be to quit. I heard in another staff meeting a derogatory story about a little Tommy Fargo who was acting up. Little Tommy was, of course, Commander, Pacific Forces, Admiral Fargo. This was shared with the rest of us as a Bill Luti lesson in civilian control of the military. It was certainly not civil or controlled, but the message was crystal.

When President Bush gave his State of the Union address, there was a small furor over the reference to the yellowcake in Niger that Saddam was supposedly seeking. After this speech, everyone was discussing this as either new intelligence saved up for just such a speech or, more cynically, just one more flamboyant fabrication that those watching the propaganda campaign had come to expect. I had not heard about yellowcake from Niger or seen it mentioned on the Office of Special Plans talking points. When I went over to my old shop, sub-Saharan Africa, to congratulate them for making it into the president’s speech, they said the information hadn’t come from them or through them. They were as surprised and embarrassed as everyone else that such a blatant falsehood would make it into a presidential speech.

When General Zinni was removed as Bush’s Middle East envoy and Elliot Abrams joined the National Security Council (NSC) to lead the Mideast division, whoops and high-fives had erupted from the neocon cubicles. By midwinter, echoes of those celebrations seemed to mutate into a kind of anxious anticipation, shared by most of the Pentagon. The military was anxiously waiting under the bed for the other shoe to drop amidst concerns over troop availability, readiness for an ill-defined mission, and lack of day-after clarity. The neocons were anxiously struggling to get that damn shoe off, gleefully anticipating the martinis to be drunk and the fun to be had. The other shoe fell with a thump on Feb. 5 as Colin Powell delivered his United Nations presentation.

It was a sad day for me and many others with whom I worked when we watched Powell’s public capitulation. The era when Powell had been considered a political general, back when he was Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, had in many ways been erased for those of us who greatly admired his coup of the Pentagon neocons when he persuaded the president to pursue UN support for his invasion of Iraq. Now it was as if Powell had again rolled military interests—and national interests as well.

Around that same time, our deputy director forwarded a State Department cable that had gone out to our embassy in Turkey. The cable contained answers to 51 questions that had been asked of our ambassador by the Turkish government. The questions addressed things like after-war security arrangements, refugees, border control, stability in the Kurdish north, and occupation plans. But every third answer was either “To be determined” or “We’re working on that” or “This scenario is unlikely.” At one point, an answer included the “fact” that the United States military would physically secure the geographic border of Iraq. Curious, I checked the length of the physical border of Iraq. Then I checked out the length of our own border with Mexico. Given our exceptional success in securing our own desert borders, I found this statement interesting. Soon after, I was out-processed for retirement and couldn’t have been more relieved to be away from daily exposure to practices I had come to believe were unconstitutional. War is generally crafted and pursued for political reasons, but the reasons given to Congress and the American people for this one were so inaccurate and misleading as to be false. Certainly, the neoconservatives never bothered to sell the rest of the country on the real reasons for occupation of Iraq—more bases from which to flex U.S. muscle with Syria and Iran, better positioning for the inevitable fall of the regional sheikdoms, maintaining OPEC on a dollar track, and fulfilling a half-baked imperial vision. These more accurate reasons could have been argued on their merits, and the American people might indeed have supported the war. But we never got a chance to debate it.

My personal experience leaning precariously toward the neoconservative maw showed me that their philosophy remains remarkably untouched by respect for real liberty, justice, and American values. My years of military service taught me that values and ideas matter, but these most important aspects of our great nation cannot be defended adequately by those in uniform. This time, salvaging our honor will require a conscious, thoughtful, and stubborn commitment from each and every one of us, and though I no longer wear the uniform, I have not given up the fight.

Karen Kwiatkowski served as Political-military affairs officer in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Under Secretary for Policy, in the Sub-Saharan Africa and Near East South Asia (NESA) Policy directorates; worked on the North Africa desk; served on the Air Force Staff, Operations Directorate at the Pentagon; served on the staff of the Director of the National Security Agency (NSA) at Fort Meade, as well as tours of duty in Alaska, Massachusetts, Spain and Italy. Kwiatkowski is the author of two books, has an MA in Government from Harvard University, MS in Science Management from the University of Alaska, and completed both Air Command and Staff College and the Naval War College seminar programs. She earned her Ph.D. in World Politics from Catholic University of America.

The new Pentagon papers

By Karen Kwiatkowski, Salon, March 10, 2004

I witnessed neoconservative agenda bearers usurp carefully considered assessments, and through suppression and distortion of intelligence analysis promulgate what were in fact falsehoods to both Congress and the executive office of the president…

In July of last year, after just over 20 years of service, I retired as a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Air Force. I had served as a communications officer in the field and in acquisition programs, as a speechwriter for the National Security Agency director, and on the Headquarters Air Force and the office of the secretary of defense staffs covering African affairs. I had completed Air Command and Staff College and Navy War College seminar programs, two master’s degrees, and everything but my Ph.D. dissertation in world politics at Catholic University. I regarded my military vocation as interesting, rewarding and apolitical. My career started in 1978 with the smooth seduction of a full four-year ROTC scholarship. It ended with 10 months of duty in a strange new country, observing up close and personal a process of decision making for war not sanctioned by the Constitution we had all sworn to uphold. Ben Franklin’s comment that the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia had delivered “a republic, madam, if you can keep it” would come to have special meaning.

In the spring of 2002, I was a cynical but willing staff officer, almost two years into my three-year tour at the office of the secretary of defense, undersecretary for policy, sub-Saharan Africa. In April, a call for volunteers went out for the Near East South Asia directorate (NESA). None materialized. By May, the call transmogrified into a posthaste demand for any staff officer, and I was “volunteered” to enter what would be a well-appointed den of iniquity.

The education I would receive there was like an M. Night Shyamalan movie — intense, fascinating and frightening. While the people were very much alive, I saw a dead philosophy — Cold War anti-communism and neo-imperialism — walking the corridors of the Pentagon. It wore the clothing of counterterrorism and spoke the language of a holy war between good and evil. The evil was recognized by the leadership to be resident mainly in the Middle East and articulated by Islamic clerics and radicals. But there were other enemies within, anyone who dared voice any skepticism about their grand plans, including Secretary of State Colin Powell and Gen. Anthony Zinni.

From May 2002 until February 2003, I observed firsthand the formation of the Pentagon’s Office of Special Plans and watched the latter stages of the neoconservative capture of the policy-intelligence nexus in the run-up to the invasion of Iraq. This seizure of the reins of U.S. Middle East policy was directly visible to many of us working in the Near East South Asia policy office, and yet there seemed to be little any of us could do about it.

I saw a narrow and deeply flawed policy favored by some executive appointees in the Pentagon used to manipulate and pressurize the traditional relationship between policymakers in the Pentagon and U.S. intelligence agencies.

I witnessed neoconservative agenda bearers within OSP usurp measured and carefully considered assessments, and through suppression and distortion of intelligence analysis promulgate what were in fact falsehoods to both Congress and the executive office of the president.

While this commandeering of a narrow segment of both intelligence production and American foreign policy matched closely with the well-published desires of the neoconservative wing of the Republican Party, many of us in the Pentagon, conservatives and liberals alike, felt that this agenda, whatever its flaws or merits, had never been openly presented to the American people. Instead, the public story line was a fear-peddling and confusing set of messages, designed to take Congress and the country into a war of executive choice, a war based on false pretenses, and a war one year later Americans do not really understand. That is why I have gone public with my account.

To begin with, I was introduced to Bill Luti, assistant secretary of defense for NESA. A tall, thin, nervously intelligent man, he welcomed me into the fold. I knew little about him. Because he was a recently retired naval captain and now high-level Bush appointee, the common assumption was that he had connections, if not capability. I would later find out that when Dick Cheney was secretary of defense over a decade earlier, Luti was his aide. He had also been a military aide to Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich during the Clinton years and had completed his Ph.D. at the Fletcher School at Tufts University. While his Navy career had not granted him flag rank, he had it now and was not shy about comparing his place in the pecking order with various three- and four-star generals and admirals in and out of the Pentagon. Name dropping included references to getting this or that document over to Scooter, or responding to one of Scooter’s requests right away. Scooter, I would find out later, was I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, the vice president’s chief of staff.

Key personnel were replaced

Co-workers who had watched the transition from Clintonista to Bushite shared conversations and stories indicating that something deliberate and manipulative was happening to NESA. Key professional personnel, longtime civilian professionals holding the important billets in NESA, were replaced early on during the transition. Longtime officer director Joe McMillan was reassigned to the National Defense University. The director’s job in the time of transition was to help bring the newly appointed deputy assistant secretary up to speed, ensure office continuity, act as a resource relating to regional histories and policies, and help identify the best ways to maintain course or to implement change. Removing such a critical continuity factor was not only unusual but also seemed like willful handicapping. It was the first signal of radical change.

At the time, I didn’t realize that the expertise on Middle East policy was not only being removed, but was also being exchanged for that from various agenda-bearing think tanks, including the Middle East Media Research Institute, the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, and the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs. Interestingly, the office director billet stayed vacant the whole time I was there. That vacancy and the long-term absence of real regional understanding to inform defense policymakers in the Pentagon explains a great deal about the neoconservative approach on the Middle East and the disastrous mistakes made in Washington and in Iraq in the past two years.

I soon saw the modus operandi of “instant policy” unhampered by debate or experience with the early Bush administration replacement of the civilian head of the Israel, Lebanon and Syria desk office with a young political appointee from the Washington Institute, David Schenker. Word was that the former experienced civilian desk officer tended to be evenhanded toward the policies of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon of Israel, but there were complaints and he was gone. I met David and chatted with him frequently. He was a smart, serious, hardworking guy, and the proud author of a book on the chances for Palestinian democracy. Country desk officers were rarely political appointees. In my years at the Pentagon, this was the only “political” I knew doing that type of high-stress and low-recognition duty. So eager was the office to have Schenker at the Israel desk, he served for many months as a defense contractor of sorts and only received his “Schedule C” political appointee status months after I arrived.

I learned that there was indeed a preferred ideology for NESA. My first day in the office, a GS-15 career civil servant rather unhappily advised me that if I wanted to be successful here, I’d better remember not to say anything positive about the Palestinians. This belied official U.S. policy of serving as an honest broker for resolution of Israeli and Palestinian security concerns. At that time, there was a great deal of talk about Bush’s possible support for a Palestinian state. That the Pentagon could have implemented and, worse, was implementing its own foreign policy had not yet occurred to me.

Throughout the summer, the NESA spaces in one long office on the fourth floor, between the 7th and 8th corridors of D Ring, became more and more crowded. With war talk and planning about Iraq, all kinds of new people were brought in. A politically savvy civilian-clothes-wearing lieutenant colonel named Bill Bruner served as the Iraq desk officer, and he had apparently joined NESA about the time Bill Luti did. I discovered that Bruner, like Luti, had served as a military aide to Speaker Gingrich. Gingrich himself was now conveniently an active member of Bush’s Defense Policy Board, which had space immediately below ours on the third floor.

I asked why Bruner wore civilian attire, and was told by others, “He’s Chalabi’s handler.” Chalabi, of course, was Ahmad Chalabi, the president of the Iraqi National Congress, who was the favored exile of the neoconservatives and the source of much of their “intelligence.” Bruner himself said he had to attend a lot of meetings downtown in hotels and that explained his suits. Soon, in July, he was joined by another Air Force pilot, a colonel with no discernible political connections, Kevin Jones. I thought of it as a military-civilian partnership, although both were commissioned officers.

Among the other people arriving over the summer of 2002 was Michael Makovsky, a recent MIT graduate who had written his dissertation on Winston Churchill and was going to work on “Iraqi oil issues.” He was David Makovsky’s younger brother. David was at the time a senior fellow at the Washington Institute and had formerly been an editor of the Jerusalem Post, a pro-Likud newspaper. Mike was quiet and seemed a bit uncomfortable sharing space with us. He soon disappeared into some other part of the operation and I rarely saw him after that.

In late summer, new space was found upstairs on the fifth floor, and the “expanded Iraq desk,” now dubbed the “Office of Special Plans,” began moving there. And OSP kept expanding.

Another person I observed to appear suddenly was Michael Rubin, another Washington Institute fellow working on Iraq policy. He and Chris Straub, a retired Army officer who had been a Republican staffer for the Senate Intelligence Committee, were eventually assigned to OSP.

John Trigilio, a Defense Intelligence Agency analyst, was assigned to handle Iraq intelligence for Luti. Trigilio had been on a one-year career-enhancement tour with the office of the secretary of defense that was to end in August 2002. DIA had offered him routine intelligence positions upon his return from his OSD sabbatical, but none was as interesting as working in August 2002 for Luti. John asked Luti for help in gaining an extension for another year, effectively removing him from the DIA bureaucracy and its professional constraints.

Trigilio and I had hallway debates, as friends. The one I remember most clearly was shortly after President Bush gave his famous “mushroom cloud” speech in Cincinnati in October 2002, asserting that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction as well as ties to “international terrorists,” and was working feverishly to develop nuclear weapons with “nuclear holy warriors.” I asked John who was feeding the president all the bull about Saddam and the threat he posed us in terms of WMD delivery and his links to terrorists, as none of this was in secret intelligence I had seen in the past years. John insisted that it wasn’t an exaggeration, but when pressed to say which actual intelligence reports made these claims, he would only say, “Karen, we have sources that you don’t have access to.” It was widely felt by those of us in the office not in the neoconservatives’ inner circle that these “sources” related to the chummy relationship that Ahmad Chalabi had with both the Office of Special Plans and the office of the vice president.

The newly named director of the OSP, Abram Shulsky, was one of the most senior people sharing our space that summer. Abe, a kindly and gentle man, who would say hello to me in the hallways, seemed to be someone I, as a political science grad student, would have loved to sit with over coffee and discuss the world’s problems. I had a clear sense that Abe ranked high in the organization, although ostensibly he was under Luti. Luti was known at times to treat his staff, even senior staff, with disrespect, contempt and derision. He also didn’t take kindly to staff officers who had an opinion or viewpoint that was off the neoconservative reservation. But with Shulsky, who didn’t speak much at the staff meetings, he was always respectful and deferential. It seemed like Shulsky’s real boss was somebody like Douglas Feith or higher.

Doug Feith, undersecretary of defense for policy, was a case study in how not to run a large organization. In late 2001, he held the first all-hands policy meeting at which he discussed for over 15 minutes how many bullets and sub-bullets should be in papers for Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. A year later, in August of 2002, he held another all-hands meeting in the auditorium where he embarrassed everyone with an emotional performance about what it was like to serve Rumsfeld. He blithely informed us that for months he didn’t realize Rumsfeld had a daily stand-up meeting with his four undersecretaries. He shared with us the fact that, after he started to attend these meetings, he knew better what Rumsfeld wanted of him. Most military staffers and professional civilians hearing this were incredulous, as was I, to hear of such organizational ignorance lasting so long and shared so openly. Feith’s inattention to most policy detail, except that relating to Israel and Iraq, earned him a reputation most foul throughout Policy, with rampant stories of routine signatures that took months to achieve and lost documents. His poor reputation as a manager was not helped by his arrogance. One thing I kept hearing from those defending Feith was that he was “just brilliant.” It was curiously like the brainwashed refrain in “The Manchurian Candidate” about the programmed sleeper agent Raymond Shaw, as the “kindest, warmest, bravest, most wonderful human being I’ve ever known.”

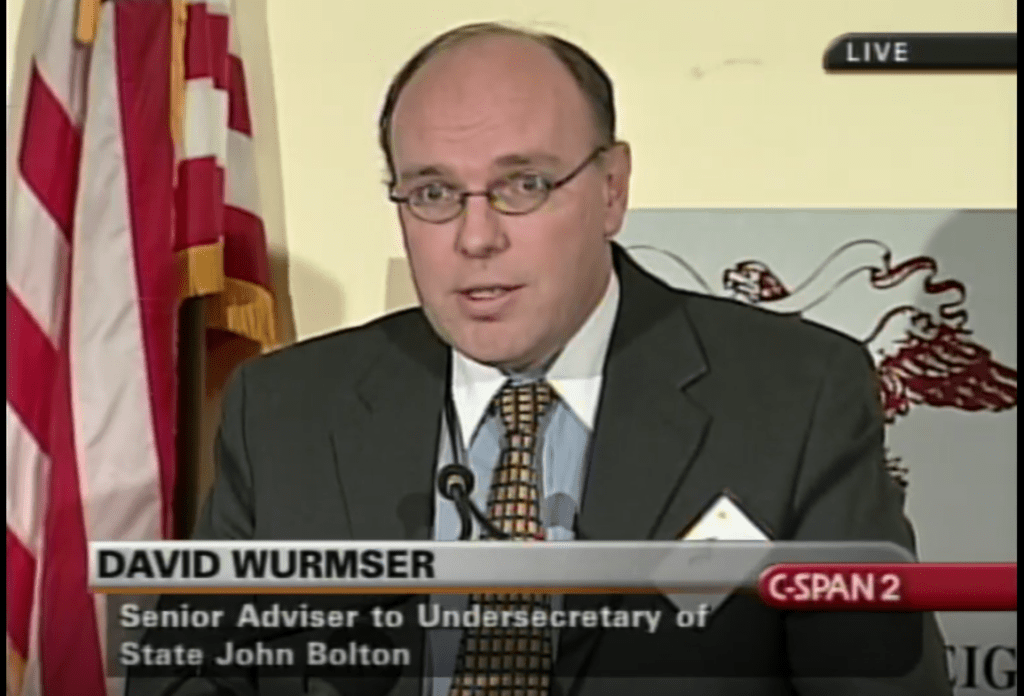

I spent time that summer exploring the neoconservative worldview and trying to grasp what was happening inside the Pentagon. I wondered what could explain this rush to war and disregard for real intelligence. Neoconservatives are fairly easy to study, mainly because they are few in number, and they show up at all the same parties. Examining them as individuals, it became clear that almost all have worked together, in and out of government, on national security issues for several decades. The Project for the New American Century and its now famous 1998 manifesto to President Clinton on Iraq is a recent example. But this statement was preceded by one written for Benyamin Netanyahu’s Likud Party campaign in Israel in 1996 by neoconservatives Richard Perle, David Wurmser and Douglas Feith titled “A Clean Break: Strategy for Securing the Realm.”

David Wurmser is the least known of that trio and an interesting example of the tangled neoconservative web. In 2001, the research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute was assigned to the Pentagon, then moved to the Department of State to work as deputy for the hard-line conservative undersecretary John Bolton, then to the National Security Council, and now is lodged in the office of the vice president. His wife, the prolific Meyrav Wurmser, executive director of the Middle East Media Research Institute, is also a neoconservative team player.

Before the Iraq invasion, many of these same players labored together for literally decades to push a defense strategy that favored military intervention and confrontation with enemies, secret and unconstitutional if need be. Some former officials, such as Richard Perle (an assistant secretary of defense under Reagan) and James Woolsey (CIA director under Clinton), were granted a new lease on life, a renewed gravitas, with positions on President Bush’s Defense Policy Board. Others, like Elliott Abrams and Paul Wolfowitz, had apparently overcome previous negative associations from an Iran-Contra conviction for lying to the Congress and for utterly miscalculating the strength of the Soviet Union in a politically driven report to the CIA.

Neoconservatives march as one phalanx in parallel opposition to those they hate. In the early winter of 2002, a co-worker U.S. Navy captain and I were discussing the service being rendered by Colin Powell at the time, and we were told by the neoconservative political appointee David Schenker that “the best service Powell could offer would be to quit right now.” I was present at a staff meeting when Bill Luti called Marine Gen. and former Chief of Central Command Anthony Zinni a “traitor,” because Zinni had publicly expressed reservations about the rush to war.

After August 2002, the Office of Special Plans established its own rhythm and cadence separate from the non-politically minded professionals covering the rest of the region. While often accused of creating intelligence, I saw only two apparent products of this office: war planning guidance for Rumsfeld, presumably impacting Central Command, and talking points on Iraq, WMD and terrorism. These internal talking points seemed to be a mélange crafted from obvious past observation and intelligence bits and pieces of dubious origin. They were propagandistic in style, and all desk officers were ordered to use them verbatim in the preparation of any material prepared for higher-ups and people outside the Pentagon. The talking points included statements about Saddam Hussein’s proclivity for using chemical weapons against his own citizens and neighbors, his existing relations with terrorists based on a member of al-Qaida reportedly receiving medical care in Baghdad, his widely publicized aid to the Palestinians, and general indications of an aggressive viability in Saddam Hussein’s nuclear weapons program and his ongoing efforts to use them against his neighbors or give them to al-Qaida style groups. The talking points said he was threatening his neighbors and was a serious threat to the U.S., too.

I suspected, from reading Charles Krauthammer, a neoconservative columnist for the Washington Post, and the Weekly Standard, and hearing a Cheney speech or two, that these talking points left the building on occasion. Both OSP functions duplicated other parts of the Pentagon. The facts we should have used to base our papers on were already being produced by the intelligence agencies, and the war planning was already done by the combatant command staff with some help from the Joint Staff. Instead of developing defense policy alternatives and advice, OSP was used to manufacture propaganda for internal and external use, and pseudo war planning.

As a result of my duties as the North Africa desk officer, I became acquainted with the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) support staff for NESA. Every policy regional director was served by a senior executive intelligence professional from DIA, along with a professional intelligence staff. This staff channeled DIA products, accepted tasks for DIA, and in the past had been seen as a valued member of the regional teams. However, as the war approached, this type of relationship with the Defense Intelligence Agency crumbled.

Even the most casual observer could note the tension and even animosity between “Wild Bill” Luti (as we came to refer to our boss) and Bruce Hardcastle, our defense intelligence officer (DIO). Certainly, there were stylistic and personality differences. Hardcastle, like most senior intelligence officers I knew, was serious, reserved, deliberate, and went to great lengths to achieve precision and accuracy in his speech and writing. Luti was the kind of guy who, in staff meetings and in conversations, would jump from grand theory to administrative minutiae with nary a blink or a fleeting shadow of self-awareness.

I discovered that Luti and possibly others within OSP were dissatisfied with Hardcastle’s briefings, in particular with the aspects relating to WMD and terrorism. I was not clear exactly what those concerns were, but I came to understand that the DIA briefing did not match what OSP was claiming about Iraq’s WMD capabilities and terrorist activities. I learned that shortly before I arrived there had been an incident in NESA where Hardcastle’s presence and briefing at a bilateral meeting had been nixed abruptly by Luti. The story circulating among the desk officers was “a last-minute cancellation” of the DIO presentation. Hardcastle’s intelligence briefing was replaced with one prepared by another Policy office that worked nonproliferation issues. While this alternative briefing relied on intelligence produced by DIO and elsewhere, it was not a product of the DIA or CIA community, but instead was an OSD Policy “branded” product — and so were its conclusions. The message sent by Policy appointees and well understood by staff officers and the defense intelligence community was that senior appointed civilians were willing to exclude or marginalize intelligence products that did not fit the agenda.

Staff officers would always request OSP’s most current Iraq, WMD and terrorism talking points. On occasion, these weren’t available in an approved form and awaited Shulsky’s approval. The talking points were a series of bulleted statements, written persuasively and in a convincing way, and superficially they seemed reasonable and rational. Saddam Hussein had gassed his neighbors, abused his people, and was continuing in that mode, becoming an imminently dangerous threat to his neighbors and to us — except that none of his neighbors or Israel felt this was the case. Saddam Hussein had harbored al-Qaida operatives and offered and probably provided them with training facilities — without mentioning that the suspected facilities were in the U.S./Kurdish-controlled part of Iraq. Saddam Hussein was pursuing and had WMD of the type that could be used by him, in conjunction with al-Qaida and other terrorists, to attack and damage American interests, Americans and America — except the intelligence didn’t really say that. Saddam Hussein had not been seriously weakened by war and sanctions and weekly bombings over the past 12 years, and in fact was plotting to hurt America and support anti-American activities, in part through his carrying on with terrorists — although here the intelligence said the opposite. His support for the Palestinians and Arafat proved his terrorist connections, and basically, the time to act was now. This was the gist of the talking points, and it remained on message throughout the time I watched the points evolve.

But evolve they did, and the subtle changes I saw from September to late January revealed what the Office of Special Plans was contributing to national security. Two key types of modifications were directed or approved by Shulsky and his team of politicos. First was the deletion of entire references or bullets. The one I remember most specifically is when they dropped the bullet that said one of Saddam’s intelligence operatives had met with Mohammad Atta in Prague, supposedly salient proof that Saddam was in part responsible for the 9/11 attack. That claim had lasted through a number of revisions, but after the media reported the claim as unsubstantiated by U.S. intelligence, denied by the Czech government, and that Atta’s location had been confirmed by the FBI to be elsewhere, that particular bullet was dropped entirely from our “advice on things to say” to senior Pentagon officials when they met with guests or outsiders.

The other change made to the talking points was along the line of fine-tuning and generalizing. Much of what was there was already so general as to be less than accurate.

Some bullets were softened, particularly statements of Saddam’s readiness and capability in the chemical, biological or nuclear arena. Others were altered over time to match more exactly something Bush and Cheney said in recent speeches. One item I never saw in our talking points was a reference to Saddam’s purported attempt to buy yellowcake uranium in Niger. The OSP list of crime and evil had included Saddam’s attempts to seek fissionable materials or uranium in Africa. This point was written mostly in the present tense and conveniently left off the dates of the last known attempt, sometime in the late 1980s. I was surprised to hear the president’s mention of the yellowcake in Niger in his 2003 State of the Union address because that indeed was new and in theory might have represented new intelligence, something that seemed remarkably absent in any of the products provided us by the OSP (although not for lack of trying). After hearing of it, I checked with my old office of Sub-Saharan African Affairs — and it was news to them, too. It also turned out to be false.

It is interesting today that the “defense” for those who lied or prevaricated about Iraq is to point the finger at the intelligence. But the National Intelligence Estimate, published in September 2002, as remarked upon recently by former CIA Middle East chief Ray McGovern, was an afterthought. It was provoked only after Sens. Bob Graham and Dick Durban noted in August 2002, as Congress was being asked to support a resolution for preemptive war, that no NIE elaborating real threats to the United States had been provided. In fact, it had not been written, but a suitable NIE was dutifully prepared and submitted the very next month. Naturally, this document largely supported most of the outrageous statements already made publicly by Bush, Cheney, Rice and Rumsfeld about the threat Iraq posed to the United States. All the caveats, reservations and dissents made by intelligence were relegated to footnotes and kept from the public. Funny how that worked.

Starting in the fall of 2002 I found a way to vent my frustrations with the neoconservative hijacking of our defense policy. The safe outlet was provided by retired Col. David Hackworth, who agreed to publish my short stories anonymously on his Web site Soldiers for the Truth, under the moniker of “Deep Throat: Insider Notes From the Pentagon.” The “deep throat” part was his idea, but I was happy to have a sense that there were folks out there, mostly military, who would be interested in the secretary of defense-sponsored insanity I was witnessing on almost a daily basis. When I was particularly upset, like when I heard Zinni called a “traitor,” I wrote about it in articles like this one.

In November, my Insider articles discussed the artificial worlds created by the Pentagon and the stupid naiveté of neocon assumptions about what would happen when we invaded Iraq. I discussed the price of public service, distinguishing between public servants who told the truth and then saw their careers flame out and those “public servants” who did not tell the truth and saw their careers ignite. My December articles became more depressing, discussing the history of the 100 Years’ War and “combat lobotomies.” There was a painful one titled “Minority Reports” about the necessity but unlikelihood of a Philip Dick sci-fi style “minority report” on Feith-Wolfowitz-Rumsfeld-Cheney’s insanely grandiose vision of some future Middle East, with peace, love and democracy brought on through preemptive war and military occupation.

I shared some of my concerns with a civilian who had been remotely acquainted with the Luti-Feith-Perle political clan in his previous work for one of the senior Pentagon witnesses during the Iran-Contra hearings. He told me these guys were engaged in something worse than Iran-Contra. I was curious but he wouldn’t tell me anything more. I figured he knew what he was talking about. I thought of him when I read much later about the 2002 and 2003 meetings between Michael Ledeen, Reuel Marc Gerecht and Iranian arms dealer Manucher Ghorbanifar — all Iran-Contra figures.

In December 2002, I requested an acceleration of my retirement to the following July. By now, the military was anxiously waiting under the bed for the other shoe to drop amid concerns over troop availability, readiness for an ill-defined mission, and lack of day-after clarity. The neocons were anxiously struggling to get that damn shoe off. That other shoe fell with a thump, as did the regard many of us had held for Colin Powell, on Feb. 5 as the secretary of state capitulated to the neoconservative line in his speech at the United Nations — a speech not only filled with falsehoods pushed by the neoconservatives but also containing many statements already debunked by intelligence.

War is generally crafted and pursued for political reasons, but the reasons given to the Congress and to the American people for this one were inaccurate and so misleading as to be false. Moreover, they were false by design. Certainly, the neoconservatives never bothered to sell the rest of the country on the real reasons for occupation of Iraq — more bases from which to flex U.S. muscle with Syria and Iran, and better positioning for the inevitable fall of the regional ruling sheikdoms. Maintaining OPEC on a dollar track and not a euro and fulfilling a half-baked imperial vision also played a role. These more accurate reasons for invading and occupying could have been argued on their merits — an angry and aggressive U.S. population might indeed have supported the war and occupation for those reasons. But Americans didn’t get the chance for an honest debate.

President Bush has now appointed a commission to look at American intelligence capabilities and will report after the election. It will “examine intelligence on weapons of mass destruction and related 21st century threats … [and] compare what the Iraq Survey Group learns with the information we had prior…” The commission, aside from being modeled on failed rubber stamp commissions of the past and consisting entirely of those selected by the executive branch, specifically excludes an examination of the role of the Office of Special Plans and other executive advisory bodies. If the president or vice president were seriously interested in “getting the truth,” they might consider asking for evidence on how intelligence was politicized, misused and manipulated, and whether information from the intelligence community was distorted in order to sway Congress and public opinion in a narrowly conceived neoconservative push for war. Bush says he wants the truth, but it is clear he is no more interested in it today than he was two years ago.

Proving that the truth is indeed the first casualty in war, neoconservative member of the Defense Policy Board Richard Perle called this February for “heads to roll.” Perle, agenda setter par excellence, named George Tenet and Defense Intelligence Agency head Vice Adm. Lowell Jacoby as guilty of failing to properly inform the president on Iraq and WMD. No doubt, the intelligence community, susceptible to politicization and outdated paradigms, needs reform. The swiftness of the neoconservative casting of blame on the intelligence community and away from themselves should have been fully expected. Perhaps Perle and others sense the grave and growing danger of political storms unleashed by the exposure of neoconservative lies. Meanwhile, Ahmad Chalabi, extravagantly funded by the neocons in the Pentagon to the tune of millions to provide the disinformation, has boasted with remarkable frankness, “We are heroes in error,” and, “What was said before is not important.”

Now we are told by our president and neoconservative mouthpieces that our sons and daughters, husbands and wives are in Iraq fighting for freedom, for liberty, for justice and American values. This cost is not borne by the children of Wolfowitz, Perle, Rumsfeld and Cheney. Bush’s daughters do not pay this price. We are told that intelligence has failed America, and that President Bush is determined to get to the bottom of it. Yet not a single neoconservative appointee has lost his job, and no high official of principle in the administration has formally resigned because of this ill-planned and ill-conceived war and poorly implemented occupation of Iraq.

Will Americans hold U.S. policymakers accountable? Will we return to our roots as a republic, constrained and deliberate, respectful of others? My experience in the Pentagon leading up to the invasion and occupation of Iraq tells me, as Ben Franklin warned, we may have already failed. But if Americans at home are willing to fight — tenaciously and courageously — to preserve our republic, we might be able to keep it.

Pentagon Office Home to Neo-Con Network

By Jim Lobe, Antiwar.com, August 7, 2003

All the political appointees have in common a close identification with the views of the right-wing Likud Party in Israel… The network led the push for war against Iraq

An ad hoc office under US Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Douglas Feith appears to have acted as the key base for an informal network of mostly neo-conservative political appointees that circumvented normal interagency channels to lead the push for war against Iraq.

The Office of Special Plans (OSP), which worked alongside the Near East and South Asia (NESA) bureau in Feith’s domain, was originally created by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and Deputy Secretary Paul Wolfowitz to review raw information collected by the official US intelligence agencies for connections between Iraqi President Saddam Hussein and al-Qaeda.

Retired intelligence officials from the State Department, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) have long charged that the two offices exaggerated and manipulated intelligence about Iraq before passing it along to the White House.

Part of a broader network of neo-conservative ideologues

But key personnel who worked in both NESA and OSP were part of a broader network of neo-conservative ideologues and activists who worked with other Bush political appointees scattered around the national-security bureaucracy to move the country to war, according to retired Lt. Col. Karen Kwiatkowski, who was assigned to NESA from May 2002 through February 2003.

The heads of NESA and OSP were Deputy Undersecretary William Luti and Abram Shulsky, respectively.

Along with Feith, all of the political appointees have in common a close identification with the views of the right-wing Likud Party in Israel.

Feith, whose law partner is a spokesman for the settlement movement in Israel, has long been a fierce opponent of the Oslo peace process, while WINEP has acted as the think tank for the most powerful pro-Israel lobby in Washington, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), which generally follows a Likud line.

Also like Feith, several of the appointees were protégés of Richard Perle, an AEI fellow who doubles as chairman until last April of Rumsfeld’s unpaid Defense Policy Board (DPB), whose members were appointed by Feith, also had an office in the Pentagon one floor below the NESA offices.

Similarly, Luti, a retired naval officer, was a protégé of another DPB board member also based at AEI, former Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich. Luti in turn hired Ret. Col. William Bruner, a former Gingrich staffer, and Chris Straub, a retired lieutenant colonel, anti-abortion activist, and former staffer on the Senate Intelligence Committee.

Also working for Luti was another naval officer, Yousef Aboul-Enein, whose main job was to pore over Arabic-language newspapers and CIA transcripts of radio broadcasts to find evidence of ties between al-Qaeda and Saddam Hussein that may have been overlooked by the intelligence agencies, and a DIA officer named John Trigilio.

Through Feith, both offices worked closely with Perle, Gingrich, and two other DPB members and major war boosters – former CIA director James Woolsey and Kenneth Adelman – in ensuring that the “intelligence” they developed reached a wide public audience outside the bureaucracy.

They also debriefed “defectors” handled by the Iraqi National Congress (INC), an opposition umbrella group headed by Ahmed Chalabi, a longtime friend of Perle, whom the intelligence agencies generally wrote off as an unreliable self-promoter.

“They would draw up ‘talking points’ they would use and distribute to staff officers for inclusion in any background papers or other documentation provided to their senior officers throughout the Pentagon, and presumably to the office of the Vice President,” said Kwiatkowski. “But the talking points would be changed continually, not because of new intel (intelligence), but because the press was poking holes in what was in the memos.”

The offices fed information directly and indirectly to sympathetic media outlets, including the Rupert Murdoch-owned Weekly Standard and FoxNews Network, as well as the editorial pages of the Wall Street Journal and syndicated columnists, such as Charles Krauthammer.

In interagency discussions, Feith and the two offices communicated almost exclusively with like-minded allies in other agencies, rather than with their official counterparts, including even the DIA in the Pentagon, according to Kwiatkowski.

Rather than working with the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, its Near Eastern Affairs bureau, or even its Iraq desk, for example, they preferred to work through Undersecretary of State for Arms Control and International Security (and former AEI executive vice president) John Bolton; Michael Wurmser (another Perle protégé at AEI who staffed the predecessor to OSP); and Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Near East Affairs, Elizabeth Cheney, the daughter of the Vice President Dick Cheney.

At the National Security Council (NSC), they communicated mainly with Stephen Hadley, the deputy national security adviser, until Elliott Abrams, a dyed-in-the-wool neo-con with close ties to Feith and Perle, was appointed last December as the NSC’s top Middle East aide.

“They worked really hard for Abrams; he was a necessary link,” Kwiatkowski told IPS Wednesday. “The day he got (the appointment), they were whooping and hollering, ‘We got him in, we got him in.'”

They rarely communicated directly with the CIA, leaving that to political heavyweights, including Gingrich, who is reported to have made several trips to the CIA headquarters, and, more importantly, I Lewis “Scooter” Libby, Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff and national security adviser.

According to recent published reports, CIA analysts felt these visits were designed to put pressure on them to tailor their analyses more to the liking of administration hawks.

In some cases, NESA and OSP even prepared memos specifically for Cheney and Libby, something unheard of in previous administration because the lines of authority in the Vice President’s office and the Pentagon are entirely separate. “Luti sometimes would say, ‘I’ve got to do this for Scooter,'” said Kwiatkowski. “It looked like Cheney’s office was pulling the strings.”

Kwiatkowski said she could not confirm published reports that OSP worked with a similar ad hoc group in Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s office.

But she recounts one incident in which she helped escort a group of half a dozen Israelis, including several generals, from the first floor reception area to Feith’s office. “We just followed them, because they knew exactly where they were going and moving fast.”

When the group arrived, she noted the book which all visitors are required to sign under special regulations that took effect after the Sep. 11, 2001 attacks. “I asked his secretary, ‘Do you want these guys to sign in?’ She said, ‘No, these guys don’t have to sign in.'” It occurred to her, she said, that the office may have deliberately not wanted to maintain a record of the meeting.

She added that OSP and MESA personnel were already discussing the possibility of “going after Iran” after the war in Iraq last January and that articles by Michael Ledeen, another AEI fellow and Perle associate who has been calling for the US to work for “regime change” in Tehran since late 2001, were given much attention in the two offices.

Ledeen and Morris Amitay, a former head of AIPAC, recently created the Coalition for Democracy in Iran (CDI) to lobby for a more aggressive policy there. Their move coincided with suggestions by Sharon that Washington adopt a more confrontational policy vis – vis Teheran.

Iran recently said it was prepared to turn over five senior al-Qaeda figures, including the son of Osama bin Laden, who are currently in its custody if Washington permanently shuts down an Iraqi-based Iranian rebel group that is listed as a terrorist organization by the State Department.

Pentagon officials, particularly Feith’s office, have reportedly opposed the deal, which had been favored by the State Department, because of the possibility that the group, the Mujahadeen Khalq, might be useful in putting pressure on Tehran.

(Inter Press Service)

Jim Lobe served as chief of the Washington bureau of Inter Press Service (the other IPS) from 1980 to 1985 and again from 1989 to 2015. Best known for his coverage of the neoconservative movement’s influence on U.S. foreign policy, he has directed LobeLog.com, which has focused primarily on U.S. Middle East policy, since 2007. In 2015, LobeLog became the first weblog to win American Academy of Diplomacy’s Arthur Ross Media Award for Distinguished Reporting and Analysis on Foreign Affairs. Proud native of Seattle, Jim graduated with Highest Honors in History from Williams College and received a law degree from the University of California at Berkeley (Boalt Hall).

RELATED

- Israel loyalists embedded in U.S. government pushed U.S. into Iraq War

- The Men From JINSA and CSP: They want not just a US invasion of Iraq but “total war” against Arab regimes.

- Pro-Israel neocons abound in Washington, and they’re calling the shots

- A War for Israel

- The Israel Lobby and the Left: Uneasy Questions

No comments:

Post a Comment