'This article looks at the dangers and opportunities that Britain faces, principally inflation,

the challenge of government spending, of maintaining a balanced budget,

trade policy and why Britain should just declare unilateral free trade.'

On current policies, the private sector is set to continue its long-term decline, with higher taxes and ever-increasing regulation. But it needn’t be so.

This article looks at the dangers and opportunities that Britain faces, principally inflation, the challenge of government spending, of maintaining a balanced budget, trade policy and why Britain should just declare unilateral free trade, foreign policy in a world where the future is American decline and a rising Russia—China partnership, and the economic craziness of the green agenda.

There is no sign that these important issues are being addressed in a constructive and statesman-like manner. Fortunately or unfortunately, rising interest rates threaten to bring forward a crisis of bank credit of such magnitude that fiat currencies are likely to be undermined. Most of the policies recommended herein should be incorporated after the banking and currency crisis has passed as part of a reset designed to avoid repeating the mistakes of big government, Keynesianism, and the socialisation of economic resources.

Decline and fall

“This is the week a government that began with such promise finally lost its soul. Its great policy relaunch is a tragic mush, proof that it no longer believes in anything, not even in its self-preservation.”

Allister Heath, Editor of The Sunday Telegraph writing in today’s Daily Telegraph 3 February

Two years ago this week, Britain formally left the EU. Yet, it is estimated there are 20,000 pieces of primary EU legislation still on the statute books. And only now is there going to be an effort to remove or replace them with UK legislation. Obviously, going through them one by one would tie the legislative calendar up for years, so it is proposed to deal with them through an omnibus Brexit Freedoms Bill.

Excuse me for being cynical, but one wonders that if the Prime Minister had not come under pressure from Partygate, would this distraction from it have got to first base? After two years of inaction, why now? And it transpires that instead of doing away with unnecessary regulations as suggested in the Brexit Freedoms Bill, legislative priority will be given to the economically destructive green agenda. This underlines Allister Heath’s comment above.

There is also irrefutable evidence that a remain-supporting civil service has continually frustrated the executive over Brexit and has discouraged all meaningful economic reform. The way the Brexit Freedoms Bill is likely to play out is for every piece of EU legislation dropped, new UK regulations of similar or even tighter restrictions on production freedom will be introduced — drafted by the civil service bureaucracy with its Remainer sympathies. For improvement, read deterioration. It will require ministers in all departments to strongly resist this tendency — there’s not much hope of that.

The track record of British government is not good. Since Margaret Thatcher was elected, successive conservative administrations have pledged to reduce unnecessary state intervention and ended up fostering the opposite. They raise taxes every time they are elected, even though they market themselves as the low tax party. While the number of quangos (quasi-autonomous national government organisations) has been reduced, in practice it is because they have been merged rather than abandoned and their remits have remained intact. Another measure of government intervention, the proportion of government spending to total GDP, has risen from about 40% to over 50% in 2020. An unfair comparison given the impact of covid, some would say. But there is little sign that the explosion of government spending will come back to former levels.

Like the unelected bureaucracy in Brussels from which the nation sought to escape, the UK’s civil service has no concept of the economic benefits of free markets. Without having any skin in the game, they believe that government agencies are in the best position to decide economic outcomes for the common good. Decades of Keynesian reasoning, belief in bureaucratic process and never having had to work in a competitive environment have all fostered an arrogance of purpose in support of increasing statist economic management. It is a delusion that will end in crisis, as it did in 1975 when under a Labour government Britain was driven to borrow funds from the IMF that were reserved for third world nations.

Against this background of restrictions to economic progress, the nation is unprepared to deal with some major issues appearing on the horizon. This article examines some of them: inflation, state spending, trade policies, foreign policies, and the economic harm from the green agenda. These are just some of the areas where policies can be improved for the good of the nation and create opportunities for greatness through economic strength.

Inflation

In common with other central banks, the Bank of England would have us believe that inflation is of prices only, failing to mention changes in the quantity of currency and credit in circulation. Yet even schoolchildren in primary education will tell you that if a cake is cut into a greater number of pieces, you do not end up with more cake; you end up with smaller pieces. It is the same with the money supply, or more correctly the quantity of currency and credit. Instead, central banks seem to believe in the parable of the feeding of the five thousand: five loaves and two fishes can be subdivided to satisfy the multitudes with some left over.

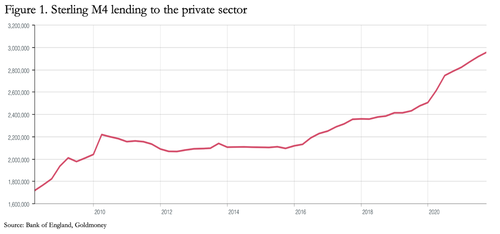

The source of an increase in the general price level is increasing quantities of currency and credit, leading to each unit buying less, just like the smaller slices of cake. And measured by the Bank of England’s M4 (the broadest measure of currency and credit) the currency cake has been subdivided into many more smaller pieces in recent times.

Figure 1 shows that M4 has increased from £1.82 trillion at the time of the Lehman failure to £2.96 trillion last September, an increase of 63%. But the rate of increase accelerated substantially in the first six months of 2020 to an annualised rate of 19.3%. This is the engine driving prices of goods higher, and to a lesser extent, services.

At that time, currency inflation was everywhere, leading to significantly higher commodity prices. The commodity inputs to industry represent sharply rising production costs, coupled with skill shortages and supply chain disruptions. But these are merely the evidence of the currency cake being more thinly sliced. Buying and installing a new kitchen in your house requires more of the smaller slices of the currency cake than it did last year.

All else being equal, there are still significant price effects to come with past currency debasements yet to work their way through to prices. And given that monetary policy is to meet rising prices by raising interest rates while still inflating, higher interest rates will follow as well. The effect on bond yields and equity prices will be beyond doubt. But all else is never equal, and the effect of higher production costs will be to close uneconomic production and put overindebted manufacturers out of business. This development is already becoming evident globally, with the post-pandemic bounce-back already fading.

Being undermined, the effect on financial collateral values is likely to make banks more cautious, reduce bank lending, and at the margin increase the rate of foreclosures. The problem is that most currency in circulation is the counterpart of bank credit. A bond and equity bear market will lead to a contraction of bank credit, triggering policies designed to counter deflation.

What will the Bank of England do? Undoubtedly, it will want to increase its monetary stimulation at a time of rising interest rates and falling financial values. The Bank will also find itself replacing contracting bank credit to keep the illusion of prosperity alive. The issuance of base currency will not be a trivial matter.

But according to the Keynesians, who can only equate price levels with consumer demand, inflation during an economic slump should never happen. Worse, it will come at a time when UK banks are highly leveraged at record levels — Barclay’s, for example, has a ratio of assets to equity of about twenty times. And as the European financial centre, London is highly exposed to counterparty risk from the Eurozone which, being in a desperately fragile condition, is a major systemic threat.

With these increased dangers so obviously present, it would behove the Bank and the Treasury to rebuild the national gold reserves, so foolishly sold down by Gordon Brown when he was Chancellor. It is the only insurance policy against a systemic and currency collapse that is becoming more likely as inflationary policies are pursued.

Government spending

As mentioned above, in 2020 the government’s share of GDP rose to over 50% and there appears to be no attempt to rein it in. And for all the rhetoric about post-Brexit Britain being an attractive place to do business, any government taking half of everyone’s income and profits in the form of taxes will fail to attract as many international businesses to locate in Britain as would otherwise be possible.

Government spending is inherently wasteful. To enhance economic performance, the solution is to cut government spending to as low as possible in the shortest possible time and to reduce taxes with it. But instead, the Treasury is seeking to cover the budget deficit, which was £250bn in the last fiscal year (11.7% of GDP) by increasing taxes without reforming wasteful government spending. The civil service has protected its practices by seeing off attempts by government appointees, such as Dominic Cummings, to remodel the civil service on more effective lines.

Critics of the Treasury’s policies say it is better to cut taxes to encourage growth which in future will generate the taxes to cover the deficit. But with the state already taking half of everyone’s income on average in taxes, the increase in the deficit while maintaining government spending will only add to inflationary pressures. The transfer of wealth from the private sector to the public sector by the expansion of currency will more than negate any benefit to the private sector from lower taxes. And the higher interest rates from yet higher price inflation will bankrupt overindebted borrowers in a highly leveraged economy.

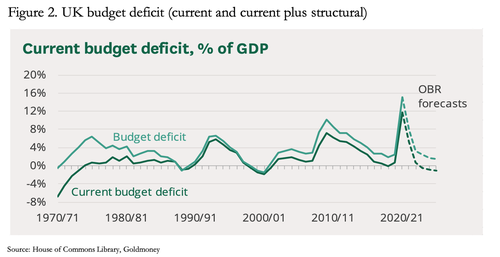

Those who think the Bank of England is clueless about finances and economics should not omit the Treasury from their criticisms. About the only thing the Treasury gets right is the necessity to eliminate the budget deficit, albeit by the wrong approach which is simply to increase the tax burden on the private sector. But in this objective it has consistently failed, as shown in Figure 2.

From the seventies, budget deficits have only been eliminated briefly in the boom times of fiscal 1989/90 and 2000/01. The OBR’s forecast of a return to near balance in 2023/24 is a demonstration of wishful thinking. On the verge of a new downturn in production brought about by unsustainable cost pressures, the deficit is likely to decline only marginally, if at all.

Budget deficits create an additional problem, because without an increase in consumer savings (discouraged by the Keynesians), national accounting shows that a twin trade deficit is the consequence. And without the trade deficit contracting, the Remainers in the establishment are bound to claim that Brexit has not delivered the benefits in trade promised by the Brexiteers.

Trade policy

Besides gaining political independence, Brexit was said to lead to an opportunity for better terms of trade than could be obtained as a member of the EU. Britain’s industrial history and heritage is as an entrepôt, whereby goods were imported, processed, and re-exported to international markets. The concept of freeports was promoted with this in mind.

The UK government has so far made laborious progress in signing trade agreements in a protectionist world. A far better approach would be to abandon trade agreements and tariffs altogether, with the sole exception of protecting some agricultural produce, for which special treatment can be justified. Today, agriculture is a small part of the economy, and the benefits to the consumer of scrapping tariffs are relatively minor, but risk fundamentally bankrupting important parts of the rural economy.

To understand why Britain should abandon trade agreements for tariff free trade, we should refer to David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage. Ricardo argued that if a distant producer was better at producing a good or service than a local one which is therefore unable to compete, then it is better to reap the benefit of the distant production and for the local producer to either find a better way of manufacturing the product, or to deploy the capital of production elsewhere.

The theory was put to the test by Robert Peel, who as Prime Minister rescinded and finally repealed the Corn Laws between 1846—1849. The consequence for the British economy was that lower food prices in what was for most of the population a subsistence economy allowed the labouring masses to buy other things to improve their standard of living.

Not only did living standards improve, but employment was created in the woollen, cotton, and tobacco industries and much else besides. Furthermore, other countries began to adopt free trade policies, which combined with sound money led to widespread economic improvement. By the First World War, over 80% of the world’s shipping then afloat, central to international trade, had been built in Britain.

The situation today is different, in that the effect of removing food tariffs from what has become a relatively small sector is far too emotive for the potential gain. This is less true of industry, despite the undoubted cries that would emanate from protectionists. But a Glaswegian is perfectly free to buy a product made in Birmingham, or to contract for a service provided from London, even if there is an equivalent available in Glasgow. But what’s the difference between our Glaswegian buying something from Birmingham, compared with Stuttgart, or Lyons, or China?

The answer is none, other than he gets more choice, and the signal sent to domestic manufacturers is they are uncompetitive. And it’s no good claiming that foreigners are unfair competition. If a foreign manufacturer is subsidised in its production, that is all to the benefit of UK consumers. Tariffs are a tax on consumers and lead to less efficient domestic production.

The benefit for Britain is that if it becomes a genuinely free trade centre, international manufacturing and service activities would gravitate to the UK, providing additional employment — all the empirical evidence confirms this is what happens. It would be a direct challenge to the EU’s Fortress Europe trade policies designed to keep foreigners out. And to the degree that tariff reform is promoted, Britain would be doing the world a favour, because as in Robert Peel’s time, other nations would likely follow suit.

The dirty truth about tariffs is that they are a tax on one’s own people as well as an unnecessary restriction of trade. Instead of recognising this truth and the evidence of its own experience, Britain is pursuing a halfway-house of laborious trade agreements. Through limited relief on taxes, the half-hearted proposal to set up free ports is an admission of the burden the government places on business in the normal course: otherwise, why are free ports an incentive? Far better to reduce taxes on all production and remove the tariff burdens on everyone.

This conservative administration started with constructive trade policies, but the permanent establishment has whittled them down to the point where they are likely to be minimised and ineffective, confirming in its Remainer yearnings that Brexit was a political and economic blunder.

Foreign policy

One of the opportunities presented by Brexit was for the UK government to think through its foreign policy agenda, and how Britain can best serve itself and the rest of the world. The history of its foreign policy might have provided a guide, though it seems to have been ignored. Instead, Britain is sticking to the Foreign Office’s and intelligence services’ status quo, which is basically to be unquestioningly allied through the five-eyes partnership with America. Admittedly, it would have been difficult to do otherwise in the wake of President Trump’s successful takedown of Huawei, spreading fear of Chinese spying in a modern version of reds under the bed.

But the reality of modern geopolitics is that Halford Mackinder’s Heartland Theory, first presented to the Royal Geographical Society in London in 1904, is coming true:

“Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland;

who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island;

who rules the World-Island commands the world.”

— Mackinder, Democratic Ideals and Reality, p. 150

There can be no doubt that the alliance between Putin’s Russia and Xi’s China together with the other members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation are proving Mackinder’s prophecy and that they are destined to become the dominant geopolitical force in the world. Therefore, Britain remains hitched in the long term to the eventual loser when it should be reconsidering its relationship with Eastern European nations, for which read Russia.

A substantial rethink over foreign policy is due, and instead of the status quo, there is profit to be had in studying the status quo ante — Britain’s foreign policies at the time of the Napoleonic wars and subsequently. Lord Liverpool was Prime Minister, with Castlereagh as Foreign Secretary and Wellington as commander-in-chief of the army. They had an iron rule never to interfere in a foreign state’s domestic policies but only to act to protect British interests. Those interests principally concern trade, and they guided foreign policy and protected British property in the colonies until the First World War.

Compared with the foreign policy principals of the nineteenth century, the support given to American hegemony in attacking nations in the Middle East and North Africa on purely political grounds has been a disaster, leading to unnecessary deaths and the displacement of millions of refugees. Some of these ventures could have been prevented if Britain had not joined in. Britain’s refusal to support a Syrian invasion after a parliamentary vote turned it down was a rare example of Britain standing up for its own interests, no thanks to a government which would otherwise have sent the troops in.

The US is dragging its heels with respect to a trade agreement with the UK, and that should be considered as well. A modern Castlereagh would take these factors into consideration in proposing a new treaty securing trade and defence considerations for both European nations and Russia, thereby respecting their sovereignties. There are enough elements in play for a sensible outcome, particularly if America is made to accept that its role in Europe is divisive and that it has no option but to accommodate compromise. The British government is in a unique position to broker a deal, if it can demonstrate political independence from all parties, including America.

The green agenda

The government’s green agenda, whereby the nation is mandated to cut carbon emissions by 78% from 1990 levels by 2035 with a target of net zero by 2050 is a deliberate policy of economic destruction. After the boost to non-fossil fuel investment, initially funded by yet more government spending, the costs imposed on the population to replace domestic heating by gas and oil with heat pumps is prohibitive and impractical. It can only be achieved by the destruction and rebuilding of swathes of existing residential and commercial properties. The energy available will be overdependent on unreliable wind and solar panel sources, and the available supply will be facing far larger demands on the grid than imposed today.

Keynesians advising the government seem to believe that all the investment and rebuilding to new ecological standards stimulates economic activity — this has been argued by them before in the context of post-war reconstruction. But then Bastiat’s broken window fallacy, whereby the alternative use of economic resources is not being considered, appears to have passed them by. The green replacement of transport logistics, which is well over 95% diesel driven, is a destruction of efficient and current capacity to be replaced by electrical powered transportation whose energy source is to be shared with all other energy demands.

The only possible solution to the problem created by climate change activism involves the rapid development of nuclear energy. But besides taking decades from drawing board to switch on, nuclear is stymied on cost grounds, with wind and solar being far cheaper on a per therm basis. Furthermore, only 16% of Britain’s electricity supply is nuclear, and almost half of that is due to be decommissioned by 2025, with only one new plant under construction.

The UK government’s green policies are propelling the nation into an energy disaster, when it has substantial fossil fuel reserves available in the form of coal and natural gas. Coal driven electricity supply has been reduced to under 3%. Instead of being phased out it should be brought back into supply production, because scrubbers remove almost all particulates and sulphates, and doubtless can be further developed to deal with CO2 emissions as well.

There are good reasons to reinstate coal and for that matter gas fracking. China and India retain and are increasing their coal powered supplies, giving them a significant energy price advantage for their own economies over the West. And while they have signed up to eventually reducing their coal dependency, it is a promise to do so at a vanishingly future date. On energy grounds alone, Britain along with other European nations are committing themselves to swapping their economic status with emerging nations, so that when the latter have fully emerged, Britain and Europe will then have the third world status.

Whatever climate change debate merits, it is an argument which is not to be confused with economics. It must be admitted that in the enthusiasm for doing away with fossil fuels and primary and reliable sources of energy, under this current government the outlook for Britain’s economy is of an accelerated decline.

The likely outcome of government policies

From what started as a government of ministers with a strong libertarian approach, two years later we see the opportunity to improve Britain’s economic consequences sadly squandered. Politically, the position is fragile, with the Prime Minister struggling to survive in the wake of the report on Partygate and the ongoing police investigation. Furthermore, he appears to have found it far easier and more pleasurable to increase spending than address wasteful government spending.

It is difficult to be optimistic, with the signs that the permanent civil service establishment remains firmly in charge and is increasing its economic and bureaucratic influence over weak ministries.

Perhaps the most important of the difficulties outlined above is monetary inflation, likely to lead to higher interest rates in the coming months. This is not a trend isolated to sterling, and even on a best-case basis whereby a Conservative government addresses the issues raised in this article, it is very likely that attempts at economic, monetary, trade policy, foreign policy, and administrative reforms will be overtaken by the repetitive cycle of bank lending contraction. So highly geared have banks in the Eurozone become, for which London acts as the principal financial centre, that rising interest rates seem sure to trigger a global banking crisis with London as an epicentre on a scale larger than that of thirteen years ago when Lehman failed.

Such an event is likely to destroy not only banking and central banking as we know it today, but currencies, the debasement of which socialising governments increasingly rely upon. Nevertheless, the issues raised in this article will remain and need to be addressed after a currency and credit crisis has passed and economic stability begins to return. The role for a British government with respect to foreign policy will become more important, particularly for post-crisis European political stability when the euro and possibly the entire Brussels construct have been destroyed. In this event the threat of another European war cannot be dismissed, and we will need the wisdom of a modern Lord Liverpool and Viscount Castlereagh.

The destruction of the fiat currency system will provide opportunities for a reset, based on the lessons learned. The post-crisis government must learn from the mistakes of past errors and be the servant of the people and not its master. It must not interfere in the economy, and keep its size to the minimum possible, taxing no more than 10—15% of everyone’s income and profits. It must restrict its role to providing a framework for contract and criminal law and the policing of the latter, as well as the defence of the realm. It must not respond to any demands for special treatment from either businesses or individuals. Individuals must take full responsibility for their own actions, and any welfare strictly limited. And most importantly, the state must ensure that currency is sound, backed by and exchangeable for gold coin.

No comments:

Post a Comment