Are Jews More or Less Racist than white gentile ethnicities? - Is the demonization of white gentiles as racists any different from demonization of Jews in the Third Reich? - What explains the enormous influence Jews have? Is it the strength that comes from their homogeneity and unity? - Is Jewish dominance an example that proves the correctness of social Darwinism, the survival of the fittest? - Kevin MacDonald discusses some of these issues.

Know the History: Classic Essays on the Jewish Question: 1850–1945

By Kevin MacDonald: Thomas

Dalton has gathered together a series of noteworthy writing on Jews in

the century preceding the end of World War II. It was a century that

began with the rise of Jews to elite status in European society

predicated on Jewish “emancipation”—e.g., freeing Jews from various

civil disabilities, such as holding public office or engaging in certain

occupations—and ended with the defeat of National Socialism in World

War II.

By Kevin MacDonald: Thomas

Dalton has gathered together a series of noteworthy writing on Jews in

the century preceding the end of World War II. It was a century that

began with the rise of Jews to elite status in European society

predicated on Jewish “emancipation”—e.g., freeing Jews from various

civil disabilities, such as holding public office or engaging in certain

occupations—and ended with the defeat of National Socialism in World

War II.

Anti-Jewish attitudes have been a common feature wherever Jews have lived for over 2000 years—in pre-Christian antiquity, in Christian Europe, and in the Muslim Middle East. The writers represented here are from a variety of European countries, in both Eastern and Western Europe. As explored Chapter 2 of my book Separation and Its Discontents, several themes underlying anti-Jewish attitudes can be discerned:

- The Theme of Separatism and Clannishness

- Resource Competition and the Theme of Economic Domination

- Jews as Having Negative Personality Traits, Misanthropy, Willingness to Exploit Non-Jews, Greed, and Financial Corruption

- The Theme of Jewish Cultural Domination

- The Theme of Political Domination

- The Theme of Disloyalty

The essays in this collection illustrate all these themes—and much else. In the following I will give examples of how these themes run through the volume as well as provide general comments on the essays. As Dalton notes in his Introduction, Jewish issues must be discussed explicitly and openly—”no side-stepping, no pussy-footing, no polite maneuvers. … But perhaps even before all this, there is a preliminary step: Know your history (2; emphasis in original).

* * *

Richard Wagner’s classic “Jewry in Music,” published under a pseudonym in 1850, illustrates a number of these themes. He describes what might be termed an instinctive German dislike for Jews: “We have to explain to ourselves our involuntary repellence toward the nature and personality of the Jews, so as to vindicate that instinctive dislike that we plainly recognize as stronger and more overpowering than our conscious zeal to rid ourselves of it” (9; emphasis in original). Reminiscent of the attitudes of many contemporary White liberals who promote the woke ideology of race and gender, the German liberalism that led to Jewish emancipation was a sort of virtue-signaling, self-deceptive idealism, divorced from real attitudes of Germans toward real Jews—”more stimulated by a general idea than by any real sympathy” (9).

Such lofty sentiments are completely missing among the Jews who have rewarded the Germans by not “relaxing one iota of their usurpation of that material soil”—to the point that “it is rather we who are shifted into the necessity of fighting for emancipation from the Jews. … [T]he Jew is already more than emancipated, he rules and will rule as long as money remains the power before which all our doings and dealings lose their force” (10; emphasis in original). He also compares contemporary Germans to the slaves and bondsmen of the ancient and medieval world.

Wagner notes Jewish chosenness (they “have a God all to themselves”) (11), as well as the related theme of separateness and clannishness: Even their physical appearance “contains something disagreeably foreign,” a difference that Jews “deem as a pure and beneficial distinction” (11). Jews have taken no part in creating German language and culture which are “the work of a historical community”—a community in which the Jew “has been a cold, hostile on-looker” (12) and presaging the contemporary theme that Jews constitute a hostile elite. As a result, the musical works of Jews cannot resonate with the German spirit and cannot “rise, even by accident, to the ardor of a higher, heartfelt expression” (13). Despite this, Jews dominate German popular music culture; they have attained “the dictatorship of public taste” (14). On the other hand, “the true poet, no matter in what branch of art, still gains his stimulus from nothing but a faithful, loving contemplation of instinctive life, of that life that only greets his sight among the Folk” (16).

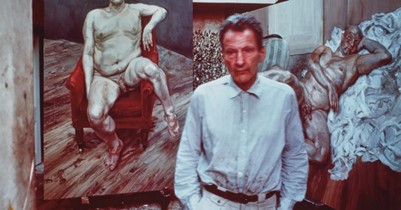

Wagner thus advocates a biological, evolutionary aesthetics rooted in the instinctive likes and dislikes of a people. Jews can’t tap into the German spirit which is necessary in order to produce a real work of art that would appeal to Germans, as opposed to a reproduction; their works “strike us as strange, odd, indifferent, unnatural, and distorted” (18). As a result, the only way such works can enter into the Western canon is if Western culture has lost its natural defenses, just as an unhealthy body is not strong enough to repel an infection that will ultimately kill it. Thus, up to the time of Mozart and Beethoven, “it was impossible that an element so foreign to that life should form part of its living organism. It is only when the inner death of a body becomes apparent that external elements have the power to seize upon it—though only to destroy it” (24). It’s thus worth noting that the rise of our new Jewish elite has resulted in a war on that which is natural, whether it’s in art (e.g., the work of Lucien Freud, Mark Rothko and Damien Hirst; art promoters like Charles Saatchi), in music (e.g., rap music with its Jewish promoters), in advertising (ubiquitously promoting miscegenation, especially for White women), or in gender (e.g., transsexualism and its consequent infertility).

Lucien Freud

Despite using a pseudonym, it became known that Wagner had authored “Jewry in Music,” and in 1869 he wrote a second part and published both in his own name. It recounts the hostility of Jews toward him and his work—which continues even now with attempts to prevent performances of Wagner’s works and cast him as a moral pariah. He notes that Leipzig, once the seat of German music and publishing, had “become exclusively a Jewish musical metropolis” (26), and asks “Whose hands direct our theaters?,” followed by a comment on the decadence on display in them.

Contemporary readers will be familiar with what happened next: Jews first ignored his essay in the hopes that it would go away, followed by “systematic libel and persecution in this domain, coupled with a total suppression of the obnoxious Jewish Question” (27). Theaters that formerly put on his operas now “exhibit a cold and unfriendly demeanor to my recent works” (34). Wagner was treated viciously not only in the German press, but also in Paris and London—but not Russia where he received “as warm a welcome from the press as from the public” (33)—a statement reflecting the fact that Jews had not become dominant in Russia and which accounts for the hostility of Western Jewish organizations toward Russia during this period. In a footnote, Dalton notes that “present-day Jews … use all varieties of libel, defamation and accusations of anti-Semitism in order to discredit their opponents. And the threat to boycott Wagner’s future operas prefigures the ‘cancel culture’ of today. Little has changed in 150 years” (27). Indeed, the vilification of Wagner continues today (see Brenton Sanderson’s 4-part series “Constructing Wagner as a Moral Pariah”).

* * *

Frederick Millingen’s “The Conquest of the World by the Jews” (1873), was written under a pseudonym, Osman Bey, presumably to avoid Jewish hostility—the same reason so many writers today use pseudonyms. After quoting Kant (1798), Lord Byron (1823), Bruno Bauer (1843) and Ralph Waldo Emerson (1860) on Jewish wealth and their financial power over rulers, Dalton notes that Millingen’s essay was “the first extended, detailed essay on the topic of Jewish global dominance” (46). Millingen proposes that the Jewish method of conquest is to dominate the material interests of their subjects and enslave them by financial oppression rather than by the physical force of a conquering army (46). This is enabled by their absorption in profit: “A Jew may stop and admire a flower … but at the same moment he is asking himself: “How much can I make from it” (emphasis in original; 48). They are a “chosen people” and with the faith that “the treasures of this world are their inheritance” (57). This “unlimited rapacity” that results in “everlasting antagonism to the rest of mankind” (49) is combined with a steely determination, “an obstinacy so inflexible that it may well be said that the Jew never gives way” (48). I’ve never read any studies on Jewish tenacity, but it’s certainly plausible: if they don’t achieve a goal in one battle (e.g., losing the immigration battle of 1924), they will continue to press the issue (winning the immigration battle in 1965, over 40 years later).

Millingen traces the history of Judaism in Europe, contending that while the Jews have always made progress toward their goal of domination, there were limits placed upon them, and it was only the French Revolution and Enlightenment ideologies that unleashed them to the full flowering of their power. In addition, Jews took advantage of technological progress—e.g., greater ease of communication between countries—so that “they are the wealthiest and most influential class of men; and have attained a position of vast power, the likes of which we do not see in all history … so that “there is not a man amongst us who is not in some way tributary to Jewish power” (64, 65). Millingen notes the wealth and the power of the Rothschilds who are able to command the subservience of European rulers, and he provides a long list of Jews admitted to the British nobility (70) and even some lower-ranking Jews in the U.S. intended to show Jewish power even there. The only exception, as also noted by Wagner, is Russia, but Russia is in the crosshairs of Jewish finance which prevents loans to the Czar while generously supporting England in its many war efforts. The prescience of Millingen’s view can be seen in that “from 1881 until the fall of the Czar, in addition to dominating the revolutionary movement in Russia, there was a Jewish consensus to use their influence in Europe and America to oppose Russia. This had an effect on a wide range of issues, including the financing of Japan in the Russo-Japanese war of 1905, the abrogation of the American-Russian trade agreement in 1908, and the financing of revolutionaries within Russia by wealthy Jews such as Jacob Schiff.” Of course, Jewish power in the U.S. vastly increased after the immigration of around 3,000,000 Eastern European Jews, and we all know what happened after the Bolsheviks attained power in the USSR.

In his section on the press, Millingen alleges that there was a meeting in 1840 in which a Jew spoke of the necessity of dominating the press, and notes that by the time of his writing, Jews owned important newspapers in France, England, Germany, and the United States, Jews were prominently involved in journalism as writers and editors, and “the book trade has passed into the hands of the Jews” (78).

Millingen concludes by describing the work of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, centered in Paris and dedicated to forming a central locus of power aimed at promoting Jewish interests around the world. As I noted in Chapter 2 of Separation and Its Discontents, the Alliance had a prominent place in the thinking of anti-Jewish authors:

“Scarcely another Jewish activity or phenomenon played such a conspicuous role in the thinking and imagination of anti-Semites all over Europe. . . . The Alliance served to conjure up the phantom of the Jewish world conspiracy conducted from a secret center—later to become the focal theme of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion” (Katz 1979, 50). Russian Jews were strongly suspected of maintaining ties with the Alliance, and anti-Semitic publications in the 1880s shifted from accusations of economic exploitation to charges of an international conspiracy centered around the Alliance (Frankel 1981).

From the late nineteenth century until the Russian Revolution, the Jewish desire to improve the poor treatment of Russian Jews conflicted with the national interests of several countries, particularly France, which was eager to develop an anti-German alliance in the wake of its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War.

Millingen concludes by noting that in the end, Jewish power depends on the power of compound interest and admonishes individuals and nations to “Keep out of debt!” (80; emphasis in original)—sage advice to say the least.

* * *

The famous Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky is represented by a section from his The Diary of a Writer (1877) that, not surprisingly, has been condemned as anti-Semitic. Again we see the themes of economic domination combined with misanthropy and willingness to exploit non-Jews. Dostoyevsky notes that Jews have exploited the recently freed serfs in Russia. This is combined with Jewish greed: “Who tied [the freed serfs] to that eternal pursuit of gold of theirs?” (84) And he notes that a similar phenomenon occurred, as relatively well-off Jews exploited freed slaves in the American South, and in Lithuania where Jews exploited the natives’ taste for vodka, with the result that rural banks were established explicitly for “saving the people from the Jews” (85).

However, Dostoyevsky adds a new idea that we see repeated endlessly in the contemporary world: that Jews attempt to lay claim to the moral high ground. Jews complain incessantly about their “their humiliation, their suffering, their martyrdom” while nevertheless controlling the stock exchanges of Europe “and therefore politics, domestic affairs, and morality of the states” (83). Dostoyevsky notes that Jews in general are much better off than Russians who were just recently relieved of the burden of serfdom and are being exploited by Jews, and he doubts that Jews have ever had any pity for Russians. Russians don’t have any “preconceived hatred” for Jews (86), while Jews have a long history of shunning the Russians—the theme of separation and clannishness, combined with hostility: “They refused to take meals with them, looked upon them with haughtiness (and where?—in a prison!) and generally expressed squeamishness and aversion towards the Russian, towards the ‘native’ people” (87). Indeed, Dostoevsky imagines how the Jews would treat the Russians if they had the power (as they did after the Bolshevik Revolution and now over the Palestinians in Israel): “Wouldn’t they convert them into slaves? Worse than that: Wouldn’t they skin them altogether? Wouldn’t they slaughter them to the last man, to the point of complete extermination, as they used to do with alien peoples in ancient times, during their ancient history?” (87), a reference to the events described in the Old Testament books of Numbers, Deuteronomy, and Joshua.

* * *

Wilhelm Marr (1819–1904) has gone down in history as the first racial anti-Semite. His signature work, The Victory of Judaism over Germanism: Viewed from a Nonreligious Point of View (1879), expresses Marr’s views on the conflict between Germans and Jews in a strikingly modern manner—that Jews are an elite that is hostile to the German people.

Marr was a journalist, and his pamphlet is expressed in a journalistic style with all the pluses and minuses that that entails. Marr’s pamphlet contains a number of ideas that agree with modern theories and social science research on Jews, as well as some ideas that are less supported but interesting nonetheless. His ideas on future events are fascinating with the 20/20 hindsight of 140 years of history.

Marr describes his writing as “a ‘scream of pain’ coming from the oppressed” (6).[1] Marr sees Germans as having already lost the battle with Jewry: “Judaism has triumphed on a worldwide historical basis. I shall bring the news of a lost battle and of the victory of the enemy and all of that I shall do without offering excuses for the defeated army.”

In other words, Marr is not blaming the Jews for their predominance in German society, but rather blaming the Germans for allowing this to happen. He sees historical hatred against Jews as due to their occupational profile (“the loathing Jews demonstrate for real work” — a gratuitously negative and overly generalized reference to the Jewish occupational profile) and to “their codified hatred against all non-Jews” (8) — the common charge of misanthropy. Historical anti-Semitism often had a religious veneer, but it was actually motivated by “the struggle of nations and their response to the very real Judaization of society, that is, to a battle for survival [also the perspective of Separation and Its Discontents]. … I therefore unconditionally defend Jewry against any and all religious persecution” (10).

Marr claims that Jews have a justified hatred toward Europeans:

Nothing is more natural than the hatred the Jews must have felt for those who enslaved them and abducted them from their homeland [i.e., the Romans; Marr seems unaware that the Jewish Diaspora predated the failed Jewish rebellions of the first and second centuries]. Nothing is more natural than that this hatred had to grow during the course of oppression and persecution in the Occident over the span of almost two thousand years. … Nothing is more natural than that they responded using their inborn gifts of craftiness and cleverness by forming as “captives” a state within a state, a society within a society. (11)

Jews used their abilities to obtain power in Germany and other Western societies: “By the nineteenth century the amazing toughness and endurance of the Semites had made them the leading power within occidental society. As a result, and that particularly in Germany, Jewry has not been assimilated into Germanism, but Germanism has been absorbed into Judaism” (11).

Marr claims that Judaism retreated in the face of “Christian fanaticism,” and achieved its greatest successes first among the Slavs and then among the Germans — both groups that were late in developing national cultures. He attributes the success of Jews in Germany to the fact that Germans did not have a sense of German nationality or German national pride (12).

This is a point that I have also stressed: Collectivist cultures such as medieval Christianity tend to be problematic for Jews because Jews are seen as an outgroup by a strongly defined ingroup; (see, e.g., here.) Moreover, a general trend in European society after the Enlightenment was to develop cultures with a strong sense of national identity where Christianity and/or ethnic origins formed a part. These cultures tended to exclude Jews, at least implicitly. An important aspect of Jewish intellectual and political activity in post-Enlightenment societies has therefore been opposition to national cultures throughout Europe and other Western societies (see, e.g., here).

Marr credits Jews with bringing economic benefits to Germany: “There is no way to deny that the abstract, money-oriented, haggling mind of the Jews has contributed much to the flourishing of commerce and industry in Germany.” Although “racial anti-Semites” are often portrayed as viewing Jews as genetically inferior or even subhuman, a very strong tendency among racial anti-Semites is to see Jews as a very talented group. Marr clearly sees Jews as an elite.

Indeed, Marr sees the Germans as inferior to the Jews and as having a mélange of traits that caused them to lose the battle to Jews:

Into this confused, clumsy Germanic element penetrated a smooth crafty, pliable Jewry; with all of its gifts of realism [as opposed to German idealism], intellectually well qualified as far as the gift of astuteness is concerned, to look down upon the Germans and subduing the monarchical, knightly, lumbering German by enabling him in his vices. (13)

What we [Germans] don’t have is the drive of the Semitic people. On account of our tribal organization we shall never be able to acquire such a drive and because cultural development knows no pause, our outlook is none other than a time when we Germans will live as slaves under the legal and political feudalism of Judaism. (14)

Germanic indolence, Germanic stinginess, convenient Teutonic disdainfulness of expression are responsible [for the fact] that the agile and clever Israel now decides what one shall say and what not…. You have turned the press over to them because you find brilliant frivolity more to your liking than moral fortitude …. The Jewish people thrive because of their talents and you have been vanquished, as you should have been and as you have deserved a thousandfold. (30)

Are we willing to sacrifice? Did we succeed in creating even a single anti-Jewish leaning paper, which manages to be politically neutral? … To de-Judaize ourselves, for that we clearly lack physical and spiritual strength.

I marvel in admiration at this Semitic people which put its heel onto the nape of our necks. … We harbor a resilient, tough, intelligent foreign tribe among us—a tribe that knows how to take advantage of every form of abstract reality. (24)

We are no longer a match for this foreign tribe. (27)

As a result of his high estimation of Jews and low estimation of Germans, Marr claims that he does not hate Jews. It’s simply a war where one side loses. The conflict between Jews and Germans is “like a war. How can I hate the soldier whose bullet happens to hit me? — Does one not offer one’s hand as victor as well as a prisoner of war? … In my eyes, it is a war which has been going on for 1800 years” (28).

Despite their long history of living together, Jews, unlike other peoples who have come to Germany, remain foreigners among the Germans —the separatism that is fundamental to Judaism as a group evolutionary strategy (and hence my titles, A People that Shall Dwell Alone and Separation and Its Discontents):

[The Jew] was a typical foreigner to them and remained one until today; and yes, his exclusive Judaism, as we shall demonstrate in what follows, shows itself even more today after his emancipation, than it did in earlier times. (13)

All other immigration into Germany … disappeared without a trace within Germanism; Wends and Slavs disappeared in the German element. The Semitic race, stronger and tougher, has survived them all. Truly! Were I a Jew, I would look upon this fact with my greatest pride. (17)

One of Marr’s most interesting observations is his proposal that Germans formed idealistic images of Jews during the Enlightenment when others had more realistic and negative views. Jews are realists, accepting the world as it is and advancing their interests based on their understanding of this reality. Judaism is characterized by particularist morality (Is it good for the Jews?). Germans, on the other hand, tend to have idealized images of themselves and others—to believe that the human mind can construct reality based on ideals that can then shape behavior. They are predisposed to moral universalism—moral rules apply to everyone and are not dependent on whether it benefits the ingroup.

This is a reference to the powerful idealist strand of German philosophy that has been so influential in the culture of the West. An illustrative example is American transcendentalism, a movement that was based on German philosophical idealism (i.e., philosophers Immanuel Kant and F. W. J. Schelling) and created an indigenous culture of critique in nineteenth-century America. This perspective resulted in overly optimistic views of human nature and tended toward radical egalitarianism; it also provided the theoretical underpinnings the abolitionist movement among elite intellectuals like Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In particular, Marr notes that, whereas prominent and influential Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire were critics of Judaism (seeing it as reactionary tribalism), in Germany the most influential writer was Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729–1781). Lessing presented a very positive image of Judaism in his play Nathan the Wise. The Jewish Nathan (Marr calls him “Rothschild” to give it contemporary relevance) makes an eloquent plea for religious tolerance—while at the same time he finances the Muslim war against the Christian Crusaders. Marr suggests that Lessing engaged in a bit of self-deception: Despite his positive portrayal of Nathan as the essence of tolerance, “Lessing could not in his subconscious self overcome the identity of Jew and servant of Mammon” (15).

The influence of Lessing was profound: “German idealism was captivated by the legend of the ring [i.e., Lessing’s metaphor for religious tolerance], but missed that Lessing’s Nathan could only be—a character from a fable” (16).

Marr suggests that instead of a fictional character like Nathan the Wise, Lessing should have seen seventeenth-century Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza as an illustration of what Judaism is really like. Whereas Nathan the Wise suggests that religious tolerance is a characteristic of Judaism, Marr interprets Spinoza’s expulsion from the Jewish community as illustrating Jewish intolerance and fanaticism in the real world—features of Judaism also noted by several contemporary writers, most notably Israel Shahak, but also including Enlightenment thinkers like Voltaire. Spinoza was hounded out of the Jewish community of Amsterdam because of his views on religion: “This truly great Jewish non-Jew had been cursed by his own tribal associates—all the way to attempted murderous assault” (16). But in the nineteenth century, “woe to the German who dares to show the Jewish masses who the great Spinoza was and what he stood for!!” (16).

Another trait of Germans that Marr sees as deleterious is “abstract individualism.” Marr states that Jewish economic success within capitalism is “in agreement with the dogma of ‘abstract individualism’ which you have accepted with enthusiasm from the hands of Judaism” (30). In other words, Marr believed that individualism was something Jews imposed on Germany, not a tendency within the Germans themselves. (Contrary to Marr’s position, I have argued that the fundamental uniqueness of European peoples is a greater tendency toward individualism than other human groups. Individualism then leads to moral universalism (Kant’s Categorical Imperative), a form of idealism, rather than the tribally-based morality of groups like the Jews.) As noted above, Marr (correctly) believed that individualistic societies are relatively defenseless against Jews, whereas societies centered around a strong collectivist religious core (e.g., medieval Christianity) or a strong sense of ethnic nationalism are more able to defend themselves.

Because of their grievances against Europeans, it is not surprising that Jews support revolution:

Who can hold it against the Jews that they happily welcomed the revolutions of 1789 and the one of 1848 and actively participated in them? “Jews, Poles and writers” was the battle cry of the conservatives in 1848. Well, of course—three suppressed factions! (16)

Following his first decisive victory of 1848 he had to—whether he wanted to or not—pursue his success further and must now attempt to ruin the Germanic, Occidental world. (28).

By 1848 Judaism had entirely ceased being a religion at all. It was “nothing else but the constitution of a people, forming a state within a state and this secondary or counter-state demanded certain material advantages for its members” (17). Marr states that Jewish emancipation only meant political equality because Jews had already achieved “a leading and dominating role” (17), and dominated all political factions except the Catholics. “The daily press is predominantly in Jewish hands, which have transformed journalism … into a business with public opinion; critique of the theater, of art in general—is to three quarters in the hands of Jews. Writing about politics and even religion is — in Jewish hands” (19). While Jews are deeply involved in creating the culture of Germany, “Judaism has been declared a subject off-limits for us Germans. … To comment on [Jewish] rituals is ‘hatred’, but if the Jew takes it upon himself to pronounce the last word in our religious and state affairs, then it is quite a different matter” (20). Of course the same phenomenon pervades the contemporary West.

Jews are particularly involved in the “culture struggle” against ultramontanism—the view that papal authority should extend over secular affairs. Ultramontanism was attacked by Jews because the Church “opposed Judaism for world domination.” Although opposition to ultramontanism was also an interest for many Germans, Jews did all the talking, and any criticism of Roman Catholicism was banned “if Israel was touched on ever so slightly!!” (20).

Jews are powerful and they will continue to obtain more power. In the end, Germans will be at the mercy of the Jews:

Within less than four generations there will not be a single office in the land, including the highest, which will not have been usurped by the Jews. Yes, through Jewry Germany will become a world power, an Occidental Palestine. … Jewry has fought the Occident for 1800 years. It has conquered and subjected it. We are the vanquished and it is quite in order that the victor chants ‘Vae Victis’ [woe to the vanquished]. (22)

The Jew has no real religion, he has a business contract with Jehovah and pays his god with statutes and formulations and in return is charged with the pleasant task of exterminating all that is not Jewish. (14)

Like several other writers represented here, Marr saw Russia as the only European nation that had resisted the Jewish onslaught. However, he believed that Russia would eventually fall by bloody revolution and this revolution would lead to the downfall of the West:

[Among European nations, only Russia] is left to still resist the foreign invasion. … [T]he final surrender of Russia is only a question of time. … Jewish resilient, fly-by-night attitude will plunge Russia into a revolution like the world might never have seen before. … With Russia, Jewry will have captured the last strategic position from which it has to fear a possible attack on its rear …. After it has invaded Russia’s offices and agencies the same way it did ours, then the collapse of our Western society will begin in earnest openly and in Jewish fashion. The ‘last hour’ of doomed Europa will strike at the latest in 100 to 150 years” (24–25).

Indeed, Jews are already taking the lead in fomenting anti-Russian policy, as in the Russian-Turkish war. For example, ideas that “the insolence of the great sea power England might be curbed” by allying with Russia were banned from the Jewish newspapers (26).

Marr is entirely pessimistic about the future, foreseeing a cataclysm:

The destructive mission of Judaism (which also existed in antiquity) will only come to a halt once it has reached its culmination, that is after Jewish Caesarism has been installed” (28).

And seemingly predicting the rise of National Socialism, he notes “Jewry will have to face a final, desperate assault particularly by Germanism, before it will achieve authoritarian dominance” (29). Marr thinks that anti-Jewish attitudes will become powerful but ultimately they will fail to fend off disaster for the Germans and the West. Marr lays part of the blame on the fact that the only people who publicly oppose the Jews conceptualize them incorrectly as a religion. As a result, responsible, informed criticism of Jews that would appeal to non-religious people and intellectual elites never appears in the press: “A catastrophe lies ahead, because the indignation against the Judaization of society is intensified by the fact that it can’t be ventilated in the press without showing itself as a most abstruse religious hatred, such as it surfaces in the ultramontane and generally in the reactionary press” (30). Nevertheless, even a “violent anti-Jewish explosion will only delay, but not avert the disintegration of Judaized society” (30).

Regarding his own mission, Marr sees himself as a soldier fighting a lost cause: “I am aware that my journalist friends and I stand defenseless before Jewry. We have no patronage among the nobility or the middle class. Our German people are too Judaized to have the will for self-preservation (32).

Marr concludes with the following:

The battle had to be fought without hatred against the individual combatant, who was forced into the role of attacker or defender. Tougher and more persistent than we, you became victorious in this battle between people, which you fought without the sword, while we massacred and burned you, but did not muster the moral strength to tell you to live and deal among your own. …

Finis Germaniae

Terrifying, but truer than ever.

* * *

The selection from Edouard Drumont includes a section from his two-volume Le France Juive (Jewish France), published in 1886. As many others have noted, Drumont claims that Jewish power derives ultimately from Jewish money (“Jews worship money”[126]), resulting in elite French non-Jews bending the knee to Jewish dominance. Drumont understood the importance of race, claiming that “the Aryan or Indo-European race is the only one to uphold the principles of justice, to experience freedom, and to value beauty” (126), but “ever since the dawn of history the Semite has dreamt constantly, obsessively, of reducing the Aryan into a state of slavery, and tying him to the land” (128). “Today the Semites believe their victory is certain. It is no longer the Carthaginian or Saracen that is in the vanguard, it is the Jew, and he has replaced violence with cunning” (129; emphasis in original).

As with Marr, Drumont claims that Aryans have several critical defects that allow Jewish domination—they are “enthusiastic, heroic, chivalrous, disinterested, frank, and trusting to the point of naivety,” while Jews are “mercantile, covetous, scheming, subtle, and cunning (129). Of the Aryan traits, disinterestedness and trust are central to the individualism of the West. For example, there is a long history of Jews approaching social science with Jewish interests in mind—the theme of The Culture of Critique—whereas Western social scientists operate in an individualist world where group interests are irrelevant. Trust is also a marker of individualism because individualist cultures rely fundamentally on the individual reputations of others rather than group membership.

a fundamental aspect of individualism is that group cohesion is based not on kinship but on reputation—most importantly in recent centuries, a moral reputation as capable, honest, trustworthy and fair. Reputation as a military leader was central to Indo-European warrior societies where leaders’ reputations were critical to being able to recruit followers (Chapter 2). And the northern hunter-gatherer groups discussed in Chapter 3 developed egalitarian, exogamous customs and a high level of social complexity in which interaction with non-relatives and strangers was the norm; again, reputation was critical. (Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition, Ch. 8).

Drumont also describes Aryans as adventurers and explorers, while Jews waited until after America had been settled by Europeans to go there in search of riches. Aryan legends are filled with noble figures engaging in heroic acts of bravery where an individual stands out from others, while Semitic tales are filled with dreams of riches (he points to Thousand and One Nights). Aryans are slow to hate but eventually he will wreak “terrible vengeance on the Semite” when they wake up—reminiscent of Rudyard Kipling’s “The Wrath of the Awakened Saxon”:

It was not part of their blood,

It came to them very late,

With long arrears to make good,

When the Saxon began to hate.

They were not easily moved,

They were icy — willing to wait

Till every count should be proved,

Ere the Saxon began to hate.

Their voices were even and low.

Their eyes were level and straight.

There was neither sign nor show

When the Saxon began to hate.

It was not preached to the crowd.

It was not taught by the state.

No man spoke it aloud

When the Saxon began to hate.

It was not suddenly bred.

It will not swiftly abate.

Through the chilled years ahead,

When Time shall count from the date

That the Saxon began to hate.

Other notable quotes:

- “The Jew’s right to oppress other people is rooted in his religion. … ‘Ask of me and I shall make the nations your heritage, and the ends of the earth your possession. You shall break them with a rod of iron, and dash them in pieces like a potter’s vessel’” (133).

- From the Talmud: “One can and one must kill the best of the goyim” (133).

- Jewish aggressiveness and self-confidence: “He has absolutely no timidity” (133); “[the Jew] either grovels at your feet, or crushes you under his heel. He is either on top or beneath, never beside” (135).

- Lack of artistic creativity: “In art they have created no original, powerful, or touching statues, no masterpieces. The criterion is whether the work will sell.” (136)

- “The strength of Jews lies in their solidarity. They all feel a common bond with one another.” (137)

- “There is one feeling that these corrupt, puffed-up people still possess, and that is hatred: of the Church, of priests, and above all the monks.” (143).

- Jewish anti-idealism: “To his mind, everything that life has to offer is material.” (144)

- The coming anti-Jewish movement: “In Germany, in Russia, in Austria-Hungary, in Romania, and in France itself where the movement is still dormant, the nobility, the middle classes, and intelligent workers—in a word, everyone with a Christian background (often without being a practicing Christian)—are in agreement on this point: The Universal Anti-Semitic Alliance has been created, and the Universal Israelite Alliance will not prevail against it.” (145; italics in original)

* * *

“The Jewish Question in Europe” (1890) was written by an anonymous author publishing in La Civilta Cattolica, an official mouthpiece of the Catholic Church. Like Drumont, it emphasizes Jewish power, but also emphasizes a newfound awakening among Europeans about Jews—“the collective outcry against the influence of the Israelites over every sector of public and social life … . Laws have been passed in France, Austria, Germany, England, Russia, Romania, and elsewhere; also, Parliaments are discussing stringent immigration quotas” (149).

The Jewish religion is now based not on the Old Testament, but on the Talmud which is thoroughly anti-Christian and which reduces Christians “to a moral nothingness which contradicts the basic principles of natural law” (150; italics in original).

Two points: the moral perspective of the Old Testament reduced all other humans to a moral nothingness, but as a staunch Catholic, the writer must suppose that until the coming of Christ, Judaism was the “only true religion” (150) and hence he must suppose that its moral philosophy was to be admired. Secondly, the conception of natural law invoked here is typical of Western moral universalism—all humans have moral worth in the sight of God—which is clearly an ideology that can easily result in maladaptive behavior, such as the immigration policies that clearly concern the writer.

Later the writer provides many other examples of ingroup morality from the Talmud, such as the Kol Nidre, said to release Jews from contracts, and the moral righteousness of usury: “It is permissible, whenever possible, to cheat a Christian. Usury imposed on a Christian is not only permissible; rather, it is a good” 159). Jewish wealth comes at the expense of non-Jews and the result has been hatred toward Jews throughout history, “the Muslims, Arabs, Persians, the Greeks, Egyptians, and Romans” (160).

The writer distinguishes between religious tolerance and civil status, quoting a prominent French lawyer who noted that “Jews everywhere form a nation within a nation; and that, although the live in France, in Germany, in England, they nevertheless do not ever become French or German or English. Rather they remain Jews and nothing but Jews” (152). Because they have no national allegiance, they can be recruited as spies, giving several examples. And because of the rise of Enlightenment values of the “rights of man” that resulted in civil status for Jews, “the dam was opened, and so, a devastating torrent let loose. In a short time, they penetrated everything, took over everything: gold, businesses, the public purse [or stock market], the highest appointments in political administration, the army and the diplomatic corps” (162). The author claims that these Enlightenment values were invented by Jews for their own benefit. (I have argued that these values were a product of the egalitarian-individualist strain of Western individualism [see here], although it’s certainly true that Jewish intellectual movements, such as the Frankfurt School, have promoted radical individualism for non-Jews while continuing their ethnic networking and group consciousness). But in any case, it’s certainly true that the Enlightenment paved the way for Jewish domination of Western societies.

As always, Jewish wealth is an issue. Here the author claims that “Jews own half the total capital in circulation in the world, and in France alone possess 80 billion francs” (169; italics in original), and that the average Jew has between 14–20 times the average wealth of a Frenchman. Astounding if true. And the author states that this wealth has allowed Jews to control the academy and the press (the latter described as an explicit goal at a Jewish conference in 1848; also noted by Millingen; see above): Using the examples of France, Austria, and Italy, he notes that “journalism and higher education are the two wings of the Israelite dragon” (171), and Christian views are actively suppressed in the schools and in the press; in France “all the irreligious and pornographic press is Jewish-owned” (172).

Jewish influence is international, as evidenced by the World Jewish Alliance, with help from Masonic groups (asserted to be anti-Christian and created by Jews; “Judaism and freemasonry are identical”). As noted, Jewish internationalism was often a target of anti-Jewish writing with the implication that Jews often supported Jewish interests in other countries at the expense of national interests of the country in which they reside.

The writer concludes by suggesting several possible solutions, including expulsion and divesting Jews of their wealth. But he claims that there will be no change until there is a return to Christianity. The elites are beyond hope. They are “the so-called ruling class, or bourgeoisie, who have been seduced, inebriated, and ground into bits between the bones of Judaism. Haven’t they refused, out of hatred for Christ, every proposed social reform? … [They] will all wind up ruined by Jews” (191).

* * *

Theodor Fritsch’s The Handbook on the Jewish Question, first published in 1887, was very popular and continued to be updated until 1944. Included here is a set of questions and answers on the topic, beginning with the commonly expressed claim among these writers that no one is criticizing Jews because of their religion and that whatever happened in the Middle Ages is irrelevant to current concerns, the main one of which is to restrict Jewish power and influence. Jews do not deserve the same rights as Germans because “they form, even today—politically, socially, and commercially—a separate community that searches for its advantage at the cost of the other citizens” (197); indeed, Judaism “operates toward the exploitation and subjugation of the non-Jewish peoples” (200), goals they pursue with “lies and deception—and money” (201).

Again, there is a complaint about Jewish moral particularism as expressed in the Talmud, a morality “that grants the name ‘man’ only to the Jew and counts the other peoples as animals” (200) who have no moral worth. Aryans are “courageous and brave”; their character manifests “uprightness, honesty, loyalty, and dedication,” while Jews exhibit “guile, slyness, hypocrisy, and lies … to which we may add harassment, insolent assertiveness, unrestricted egoism, ruthless cruelty, and excessive sexual desire (205).

Fritsch lists a variety of negative consequences—e.g., moral depravity promoted by the Jewish press—and Jews “are to blame, through their financial influence and their unscrupulous desires, for the loosening of society in every respect” (202). “They have thrown even governments into the chains through cunning financial operations and made them dependent on the mercy of Jewry” (203).

Fritsch notes that there are indeed many distinguished Jews but that any Jew with some talent will be intensely promoted by other Jews, while a talented German who does not show obeisance to Jews is “ignored with silence and does not succeed” (208). Presaging Andrew Joyce’s work on Spinoza, Fritsch notes that Spinoza’s reputation and the reputations of other famous Jews (Mendelssohn, Heine) “have been similarly exaggerated by Jewish publicity” (209).

Finally, Fritsch claims that the Jewish question can only be solved if they emigrate to their own land; if Jews remain in Germany, they should be severely restricted in their economic pursuits (only manual labor and agriculture); miscegenation must be prohibited.

* * *

Hitler is represented by his first written statement on Jews, composed as a 30-year-old in 1919. As do the others reviewed here, he sees the Jewish problem not as religious but as racial and political—a problem that must be confronted by understanding the facts, what he terms “rational anti-Semitism,” rather than simply appealing to emotions. Rational anti-Semitism leads to “a systematic and legal struggle against and eradication of, the privileges the Jews enjoy over the other foreigners living among us” (213). He emphasizes the racial purity of the Jews and that their overriding concern is with accumulating wealth, while Germans believe that moral and idealistic goals are important as well.

It is the centrality of wealth without moral principles “allow the Jew to become so unscrupulous in his choice of means, so merciless in his use of his own ends” (212). Besides wealth, Jewish power derives from their influence on the media and its ability to mold public opinion. “The result of his works is racial tuberculosis of the nation” (213).

Restructuring the state is insufficient. What must happen is “a rebirth of the nation’s moral and spiritual forces” (213). However, current leaders understand that “they are forced to accept Jewish favors to their private advantage and to repay these favors” (214)—a statement that could equally apply to the current leaders of Western countries.

* * *

As noted, Theodor Fritsch’s Handbook on the Jewish Question (1887) continued to be updated until 1944. “The Core of the Jewish Question” is from a 1923 edition. He characterizes Judaism as “something alien, hostile, and unassimilable among all nations” (217). “They are not only a separate state but a race that is closed within itself” (219), and he cites Tacitus’s claim that Judaism represents “a hatred of the entire human race” (221). He blames them for “the stab in the back” that ended World War I and for the communist revolutions that shook Germany during that period. Fritsch also emphasizes Jewish economic power and their influence in the press. “Above all, … the press in Jewish hands gave a suitable means to radically falsify German thought and feeling and to disseminate among the masses all sorts of erroneous ideas” (224). He claims that when there was natural unrest among the proletariat because of dispossession brought about by the Jews, Jews took control of socialist movements, mentioning Marx and Ferdinand Lassalle, and succeeded in not mentioning the role of Jews in the dispossession of the workers. Fritsch’s proposed solution: their own state.

* * *

* * *

Heinrich Himmler is represented by “The Schutzstaffel [SS] as Anti-Bolshevist Combat Organization.” Himmler identifies Judaism with Bolshevism, interpreted as a recurrent pattern where Jews plot against the people the live among, using the story of Esther in the Old Testament, which records the slaughter of over 75,000 Persians, as paradigmatic. He recounts several historical examples, but emphasizes the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and its aftermath. “For Bolshevism proceeds always in this manner: The heads of the leaders of a people are bloodily cut off, and then it turns into political, economic, scientific, cultural, intellectual, spiritual, and corporate slavery” (245). Thereafter the rest of the people degenerate due to race mixing and eventually they die out. Himmler praises Hitler for stopping this process in Germany, but of course it can certainly be argued that such a process is well underway in present-day Germany.

Himmler discusses the racial criteria for membership in the SS—“the physical ideal, the Nordic type of man” (252)—and he discusses several requirements of SS men, such as marriage that must be undertaken with a concern for one’s ancestors, “the eternal origins of its people” (256).

* * *

The American poet Ezra Pound’s essay “The Jews and This War” (1939) gives a good summary of historical Jewish communities which were dominated by an intermarrying elite (often called “court Jews”) with close connections to the aristocracy which they served in a variety of functions, such as in finance and tax farming. He correctly notes that these Jewish communities (“Kahals”) were well-organized, taxed their members, and could ostracize Jews who dissented from community policy. Pound believes that “today’s Kahal is centered on Wall Street, with branch offices in London and Paris” (265), and “the complex of Roosevelt’s governing instincts are those of the Kahal. In our times, England and France are governed as the Kahal would rule them” 266). While praising the “Nazi and fascist programs” as “based on European dispositions and beliefs that move to ever higher levels of development,” the American spirit “is but a dark and profaned memory, one that we Americans have a duty to pull out of the grave, hidden under piles of trash” (266–267). He concludes with a call to liberty: “Freedom is not a right; it is a duty” (267).

* * *

Robert Ley, described by Dalton in his introduction as “one of the brightest and best educated leaders of NS Germany” (269), is represented with his 1941 essay “International Melting Pot or United Nation-States of Europe?”—a prescient essay on the globalist future of Europe if Germany loses the war. He regarded Jews as a mongrel race resulting from breeding with many peoples (not supported by recent population genetic research)—a race that had evolved into a parasite. Germans on the other hand are a pure race that the Jews want to destroy: “the Jew had to drag down the ideals of other men to blur the gap between themselves and the pure races” (271) and to destroy nations which he sees as racially homogeneous entities. The League of Nations, “which ought to be called the Melting Pot, gave Jewry its final triumph. Here all nationalist promptings and all ethnic and racially conditioned characteristics of state and law were condemned as abominations” (274). “We National Socialists base our worldview on the natural laws of race, heredity, the biological laws of life, and the laws of space and soil, energy and action” (275). On the other hand, England is “governed mostly by the Jew and his money” (278), and Ley recounts post-World War I atrocities against Germany enacted by “the masters of Versailles” who are “slaves of the Jew, in the service of Freemasonry and international Marxism” aiming to destroy Germany. Much of the essay is directed at working-class Germans warning them not to be seduced by socialist ideas such as the international proletariat (“international romanticism”[282]) that prioritizes class interests over racial/ethnic interests: “The slogan of international solidarity of the working class was the greatest fraud and the basest lie that the Jew ever concocted” (281).

* * *

Theodore N. Kaufman, a Jewish businessman, wrote “Germany Must Perish” (1941) calling for the extermination of the German people. It did not have much impact in the U.S. when first published, but, after Goebbels used it as proof of a genocidal plan on the part of the allies, notices began to appear in the American media. Kaufman’s screed is indeed genocidal in intent, based on the claim that Germany is “at war with humanity” (289). Nothing less than a “TOTAL PENALTY” (289; emphasis in original) is called for. “Germany must perish forever! In fact—not in fancy” (289). This solution must apply to all Germans whether or not they agreed with their leaders. Sterilization of both sexes would accomplish the goal and could be carried out within “three years or less” (308).

* * *

Wolfgang Diewerge’s 1941 essay “The War Goal of World Plutocracy” is a comment on Kaufman’s booklet. Diewerge, a top aide to Goebbels, falsely claims that Kaufman is well-connected—“no fanatic rejected by world Jewry, no insane creature, but rather a leading and widely known Jewish figure in the United States” (312) and a member of Roosevelt’s “brain trust.” And he claims that Kaufman’s view “is the official opinion of the leading figures of world plutocracy.” Diewerge is happy the booklet has been published because it makes clear to Germans what is at stake in the war, and he reminds his readers of the Jewish role in the Soviet mass murders, “and now during the great battle for freedom in the East, Jewish commissars with machine guns stand behind the Bolshevist soldiers and shoot down the stupid masses if they begin to retreat” (325).

His chilling conclusion: “It is not a war of the past, which can find its end in the balancing of interests. It is a matter of who shall live in Europe in the future: the white race with its cultural values and creativity, with its industry and joy in life, or Jewish sub-humanity ruling over the stupid, joyless enslaved masses doomed to death” (328). One thinks of the Great Replacement and Mayorkas’s open border policy allowing millions of uneducated, impoverished non-Whites in the U.S—migrants who will be indoctrinated to hate Whites. The same thing is happening throughout the West.

* * *

The final essay is Heinrich Goitsch’s “Never!,” written in 1944 when it was apparent that Germany would be defeated. As Dalton notes in his Introduction, it was “a kind of final plea to the German people, to keep fighting, to keep up morale, and to struggle until the bitter end” (331). It includes dire foreboding of the consequences of defeat, quoting several prominent sources as desiring the end of the German people, including the notorious Morgenthau Plan, proposed by U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau, Jr., calling for the de-industrialization of Germany—a plan that would have meant millions of deaths by starvation—and a fantasy of Soviet-Jewish propagandist Ilya Ehrenberg in which “Germany finally ceased to exist. Of its 55 million inhabitants, at most 100,000 remain.” He also notes a pre-war statement of the Alliance Israelite Universelle, the international Jewish organization established in Paris, that “This German-Aryan people must vanish from history’s stage.”

Conclusion

This is an important collection. The main takeaway is that the criticisms of Jews have been remarkably consistent over this period, and indeed, many can be seen throughout the history Jews in the West as noted in the beginning of this essay. However, there was a definite shift with the onset of the Enlightenment. Several of these writers note that the Enlightenment allowed the Jews unparalleled opportunities that had not been available previously, because, in general, Jews were at least somewhat constrained in their ability to dominate societies economically. The general picture prior to the Enlightenment was that Jews made alliances with corrupt non-Jewish elites and were allowed to exploit the lower orders of society via practices such as usury and tax farming in return for giving the aristocracy a cut, although there certainly were exceptions, such as Louis IX of France (St. Louis) who abhorred the effects of Jewish economic exploitation on his subjects.[2] After the Enlightenment, Jews continued to make alliances with non-Jewish elites but there were many more economic niches available, and Jews rapidly advanced throughout Western societies, including in the universities and in political culture which had been closed off to them.

Particularly important is that the nineteenth century saw the rise of mass media and the ability of Jews to dominate or at least have a major influence on the media environment and on the culture at large—a major complaint of several writers who saw Jewish cultural influence as entirely negative, including their role in cultural criticism in the arts and in discussions of religion, denigrating the history and accomplishments of the traditional non-Jewish culture, disseminating of pornography, and penalizing individuals who criticize Jewish influence, Richard Wagner being the exemplar of the latter.

I was particularly struck by Dostoevsky’s comment that Jews attempt to lay claim to the moral high ground, complaining incessantly about their “their humiliation, their suffering, their martyrdom” while nevertheless controlling the stock exchanges of Europe “and therefore politics, domestic affairs, and morality of the states” (83). Seizing the moral high ground was impossible for Jews in traditional Western cultures where the main influences were the Church and aristocratic culture. But because of the rise of mass-circulation newspapers and the influx of Jews into academia, Jewish claims to the moral high ground pervade the contemporary West where the holocaust narrative is ubiquitous in all forms of media and throughout the educational system, while, as in Dostoevsky’s time, on average Jews are far better off than other citizens.

Such appeals to the moral high ground are uniquely effective in the West as an individualist culture—an important theme of Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition where reputation in a moral community rather than kinship forms the basic social glue . As a dominant cultural elite, Jews are able to establish the dominant moral community via their influence on the media and academic culture. In the contemporary West, that means inculcating White guilt, not only for the holocaust (seen as the inevitable outcome of the long history of anti-Semitism in Western culture), but also for the West’s history of slavery and conquest (seen as uniquely evil rather than a human universal—while ignoring the West’s role in ending slavery and generally advancing the areas they colonized).

The weakness of individualism and its concomitant traits in competition with Jews is a recurrent theme. For example, Jews are realists about their interests and rationally evaluate others in terms of their interests; they have a high degree of solidarity. On the other hand, Germans are idealistic, acting on moral values that apply to everyone, and they are trusting in the good intentions of others, often believing that Judaism was just another religion rather than a state within a state and having very different interests than Germans and indeed, hostile to them.

A repeated theme is the centrality of Jewish wealth for understanding Jewish influence. Particularly standing out is Drumont’s comment on the obeisance of the French nobility to the wealthy Jews who had nothing but contempt for them and eagerly anticipated the downfall of the gentile aristocracy that would ultimately be servants to the Jews. “What brings these representatives of the aristocracy under [Rothschild’s] roof? Respect for money. What will they do there? Kneel before the Golden Calf” (126). Needless to say, from fawning politicians dependent on Jewish campaign contributions, to virtually anyone who wants to get ahead or maintain their position in the culture of today’s West, it’s the same now. Just ask Kanye West.

Notes

[1] The page numbers in the section on Wilhelm Marr are from a different translation; see: http://www.kevinmacdonald.net/Marr-Text-English.pdf; see also: Kevin MacDonald, “Wilhelm Marr’s The Victory of Judaism over Germanism Viewed from a Nonreligious Point of View, The Occidental Observer October 10, 2010). https://www.theoccidentalobserver.net/2010/10/10/wilhelm-marrs-the-victory-of-judaism-over-germanism-viewed-from-a-nonreligious-point-of-view/

[2] From Separation and Its Discontents, Ch. 4: King Louis IX of France (Saint Louis), who lived like a monk though one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in Europe, was a particularly zealous warrior in carrying out the Church’s economic and political programs. Louis attempted to develop a corporate, hegemonic Christian entity in which social divisions within the Christian population were minimized in the interests of group harmony. Consistent with this group-oriented perspective, Louis appears to have been genuinely concerned about the effect of Jewish moneylending on society as a whole, rather than its possible benefit to the crown—a major departure from the many ruling elites throughout history who have utilized Jews as a means of extracting resources from their subjects. An ordinance of 1254 prohibited Jews from engaging in moneylending at interest and encouraged them to live by manual labor or trade. Louis also ordered that interest payments be confiscated, and he took similar action against Christian moneylenders (see Richard 1992, 162). Although there is no question that Louis evaluated the Jews negatively as an outgroup (as indicated, e.g., by his views that the Talmud was blasphemous, and by his “habitual reference to the Jews’ ‘poison’ and ‘filth’ ” [Schweitzer 1994, 150]), Louis was clearly most concerned about Jewish behavior perceived as exploitative rather than simply excluding Jews altogether because of their outgroup status. A contemporary biographer of Louis, William of Chartres, quotes him as determined “that [the Jews] may not oppress Christians through usury and that they not be permitted, under the shelter of my protection, to engage in such pursuits and to infect my land with their poison” (in Chazan 1973, 103). Louis therefore viewed the prevention of Jewish economic relations with Christians not as a political or economic problem but as a moral and religious obligation. Since the Jews were present in France at his discretion, it was his responsibility to prevent the Jews from exploiting his Christian subjects. Edward I of England, who expelled the Jews in 1290, appears to have held similar views on royal responsibility for the well-being of his subjects (Stow 1992, 228–229).

Additional: http://www.kevinmacdonald.net/SlezkineRev.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment