“We have to either change our fertility practices and patterns, or we have to accept that the economy will shrink, we will be short of labour.”

Authored by Chris Summers and Lee Hall: Britain needs to raise its fertility rates or face a stark choice between economic decline or rising levels of immigrant labour, says one of the country’s most prominent population experts.

Demographer and author Paul Morland said if British people did not start having more children the country faced a “demographic nightmare” like Japan, which has seen a shrinking and ageing population which threatens its economic future.

Speaking to NTD’s Lee Hall for the “British Thought Leaders” programme, Mr. Morland said fertility rates in Britain meant the population would eventually decrease, as would the working-age population, who contribute the prosperity to a nation.

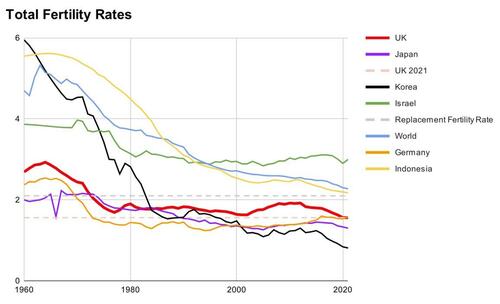

In 2020 Britain’s total fertility rate (TFR)—the number of children born per woman—stood at 1.58 in England and Wales, and was 1.29 in Scotland. That compared to 2.93 in the UK at the end of the Second World War.

A country’s population will start to decrease if its TFR is below 2.1 and Mr. Morland pointed out that in South Korea their fertility rate was 0.9 and in Japan, although it was slightly higher at 1.2, it had been lower for longer and was starting to damage their economic performance.

In his latest book, “Tomorrow’s People: The Future of Humanity in 10 Numbers,” he described it as a “trilemma.”

Britain Faces a ‘Trilemma’

Mr. Morland said: “So the trilemma is, you can have two out of three things but not all three. You can have a growing economy, which requires some sort of growing workforce; you can have a low fertility rate; and you can have ethnic homogeneity and continuity, but you can’t have all three of those.”

He said the Japanese people had chosen not to have large families but had also rejected large-scale immigration, and their economy is no longer, “the rising sun that it was in the ’70s and ’80s.”

Mr. Morland said:

“You can go the British route, saying we don’t want very large families, we’re not really prepared to replace ourselves. But we do want labour and we want economic growth. And that requires very fast immigration, and very rapid ethnic changes we’ve seen in the UK.”

He said:

“If in Britain, people don’t want immigration, and want to bring it down, I think they have to understand the consequences, and the consequences are we are already short of labour in almost every sector, despite the fact we have pretty sluggish growth, and we have a million people coming in gross per year.”

Mr. Morland said:

“If we are going to say we want slower growth in the immigrant population and a more stable ethnic situation in the country, and the population which defines itself as white British remaining as a majority, then we have to either change our fertility practices and patterns, or we have to accept that the economy will shrink, we will be short of labour.”

Total fertility rates trends in selected countries. (Data Source: World Bank. Contains open data licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license)

He said: “How long will anti-immigrant sentiment in the country remain when people find there’s no bus, there’s no one to make an appointment with at the health service, no one to drive the tankers to the petrol station?”

Mr. Morland said the prime minister of Japan, Fumio Kishida, had gone so far as to warn of “societal collapse” if the Japanese did not raise their fertility rate.

Last month the Japanese government pushed through a $25 billion package of measures to try and boost the birth rate.

Governments can ‘Only do so Much’

But Mr. Morland said governments could “only do so much”, for example by tackling the cost of housing and childcare, and he said there was evidence even in countries like Germany where childcare is much cheaper, fertility rates were still very low.

He said that, at the end of the day, fertility rates depend on how much people in a society value children and having a family.

Asked to forecast Britain’s future, Mr. Morland said:

“My guess is that … I don’t think we’re going to shift our fertility rates, in fact on the contrary. When I look at the values of Generation Z, and the priorities they have, and their outlook on the world I don’t associate that with higher fertility. I associate it with low fertility.”

“That’s across all our communities. It’s not just white British people. It’s Hindus, Sikhs, it’s Afro-Caribbeans. Very few of our communities have got higher fertility rates,” he added.

Mr. Morland said: “I would like to think that after density rate can pick up and then in 20 or 30 years’ time we can have British-born people of all backgrounds and all races and all ethnicities filling our needs for the economy in the workplace. I suspect that that won’t happen.”

“If it doesn’t happen, then we will either need to accept the dislocation of the lack of labour, or ever-growing numbers of immigrants from where we can get them, and we just assumed we can hoover them in according to our requirements, but that will get harder and harder,” he added.

Children displaced from Gatawa town in Sabon Birni County in Nigeria—which has one of the world’s highest fertility rates—on July 14, 2021 (Mansur Isa Buhari)

Mr. Morland said one of the few places in the world where fertility rates are still high is Africa and he said the rising population of sub-Saharan Africa would have a huge impact on the globe.

“Particularly in central and west Africa, we’re going to see very, very significant demographic growth in the next 20, 30, 40 years, while the rest of the world goes into a demographic decline. So the future is much more Africa and I argue that that means that everything’s going to be different,” he said.

Sub-Saharan Africa made up about 7 percent of the world’s population in 1950 but he said it was hurtling towards 25 percent of the globe, and could even reach 35 percent by 2100.

Mr. Morland said Africa would play a much bigger role on the world stage but he said it was not clear, “which countries are going to be the stars, who are going to manage to turn this opportunity into economic growth and development, and which are going to be basket cases.”

No comments:

Post a Comment