“It is a fundamental principle that legal proceedings should not be used as an instrument to oppress another.”

A ruling is not expected for weeks. The two judges on the High Court, Lord Chief Justice Ian Duncan Burnett and Lord Justice Timothy Holroyde, must decide whether District Judge Vanessa Baraitser applied the law correctly in finding that it would be oppressive to extradite a highly suicidal Assange to a harsh U.S. prison.

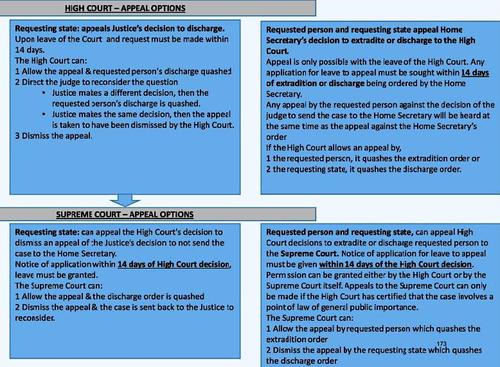

The judges can make one of five possible decisions, according to section 28 (e) of the Senior Courts Act 1981:

- they can uphold the first court’s decision and dismiss the U.S. appeal;

- they can allow the U.S. appeal and overturn the order not to extradite;

- they can send the case back to magistrate’s court with instructions on following the law;

- they can amend the ruling.

The fifth possibility is that the two judges fail to agree on a decision and a new High Court panel would rehear the U.S. appeal.

What the High Court is Weighing

Burnett and Holroyde must essentially decide if a) Assange is too ill and too prone to suicide to be extradited and b) whether they believe U.S. promises that Assange will not be put into extreme isolation in a U.S. prison.

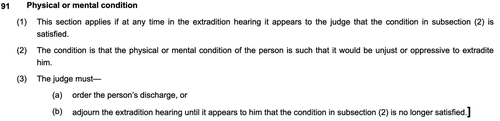

Specifically, the judges must determine whether Baraitser misapplied the law in her January decision to block Assange’s extradition. The U.S. appeal argues that Baraitser wrongly applied Section 91 of the U.S.-U.K. Extradition Treaty and that had she properly done so, she would not have discharged Assange.

What the Treaty Says

Section 91 states:

To convince the High Court that Assange is mentally fit for extradition, the U.S. wants to throw out the testimony of expert defense witness Dr. Michael Kopelman on a technicality: that he initially withheld the name of Assange’s partner Stella Moris and the existence of their two children from his preliminary report to the court.

In her judgement, Baraitser said that that though this was concerning, it was understandable in light of testimony that a C.I.A.-contracted Spanish security firm had spied on Assange and Moris at the Ecuador embassy in London. The U.S. was well aware of the existence of the children six months before Assange’s September 2020 extradition hearing.

The U.S. also argued at the High Court that two expert witnesses for the prosecution testified that Assange was neither seriously ill nor suicidal, though Consortium News reported that those witnesses actually agreed to an extent that Assange was on the autistic spectrum with Asperger’s Syndrome, which makes one nine times more likely to commit suicide.

So the High Court judges must decide whether Kopelman’s “understandable” concealment of Moris and the children rises to an egregious enough offense to disqualify Kopelman’s testimony about Assange’s mental condition. The judges must also weigh the other testimony of defense and prosecution expert witnesses about Assange’s mental condition.

Will the judges be convinced that Baraitser incorrectly found extradition “oppressive” and that they should overturn her decision?

Will Judges Trust US Assurances?

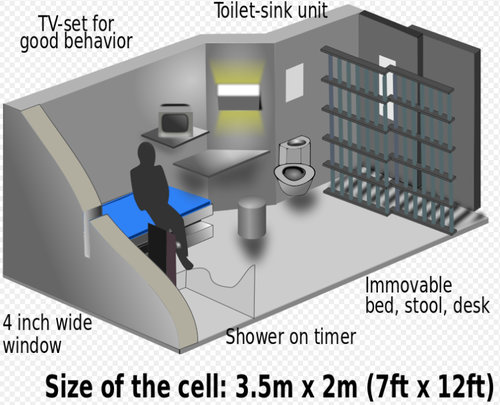

The judges must also decide whether U.S. assurances to not mistreat Assange in a U.S. prison are trustworthy. Washington has promised not to put Assange under Special Administrative Measures (SAMS) or to send him to isolation at the ADX Florence prison in Colorado.

Assange’s lawyers argued those assurances should have been given before Baraitser’s judgement and not afterward. The U.S. contended that Baraitser should have notified them of her provisional view on Section 91 before her judgement so that the assurances could have been made then.

Prosecutor James Lewis also argued that there was precedence for providing assurances after a judgement is made. He vowed that the U.S. has never broken its word in a diplomatic assurance.

Assange’s lawyers pointed to cases where the U.S. had indeed broken its word. Amnesty International has called the assurances “inherently unreliable”. In any case there is no dispute that the assurances are conditional: the U.S. said it reserves the right to change its mind: if Assange “does something” to threaten U.S. national security they could then put him into harsh isolation.

POSSIBLE OUTCOMES:

1. The US Appeal is Dismissed, Assange Wins

If the court rejects the U.S. appeal and upholds the lower court’s decision, the United States would have a decision to make. It can apply to appeal the High Court’s ruling to the U.K. Supreme Court, which may or may not take the case after the first appeal was lost. Or the U.S. can admit defeat and drop the charges, as it did in the Lauri Love case.

Vice President Joe Biden told Meet the Press in December 2010 that unless the government could catch Assange redhanded taking part in stealing classified documents, it could not indict Assange. An Espionage Act charge against him for passively receiving documents and publishing them was off the table.

And indeed the Obama-Biden administration did not indict Assange. It was unable to come up with evidence of Assange stealing documents and shied away from a collision course with the First Amendment that an espionage charge would bring.

The Donald Trump administration, however, did indict Assange, evidently unconcerned about the First Amendment. It also relied on perjured testimony to try to prove Assange was involved with hacking. If President Biden sticks with what he said when he was vice president, he would drop the case if the U.S. loses. However the Biden administration had the option to drop the Trump appeal and didn’t.

That’s likely because two things have changed since 2010: Democrats still blame WikiLeaks for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 defeat to Trump because it released verified Democratic Party emails that showed corruption in the party. As the head of the party, Biden is likely under pressure from top Democrats not to drop the case, which they would probably consider heresy.

The second thing that happened was WikiLeaks‘ release of Vault 7 in 2017, the largest ever leak of C.I.A. materials. It was what led then C.I.A. Director Mike Pompeo to seriously consider kidnapping or killing Assange. Though those nefarious plans have for the moment probably been shelved as Assange languishes in Belmarsh Prison, the current C.I.A. leadership, still aggrieved, would no doubt also be pressuring Biden not to drop the case.

Because Biden has vowed that his Justice Department is independent from White House influence, in this case at least he could easily evade party and intelligence pressure by leaving it up to Attorney General Merrick Garland to decide whether to pursue an appeal to the U.K. Supreme Court, or drop the case and let Assange go.

If the U.S. loses and appeals to Britain’s highest court, the question of whether Assange can be released on bail would again arise. After Baraitser barred extradition and “discharged” Assange, she refused to allow him bail because she ruled he was a “flight risk” and threw him back in the slammer.

This time might be different, however. Gabriel Shipton, Assange’s brother, told Consortium News that after Assange spends two years in jail on remand his lawyers can ask the European Court of Human Rights to grant him bail. Assange has been in Belmarsh on remand since September 2019. Shipton expects the European court to rule in his brother’s favor, but it is uncertain whether British authorities would honor it.

2. The US Appeal is Allowed, Assange Loses

Assange lawyer Jen Robinson told Australian TV last month that if Assange loses, he will apply for an appeal to the U.K. Supreme Court. This could add months more to the legal process and if Assange is not granted bail after the High Court decision, it would mean he’d be condemned to further imprisonment.

Assange’s lawyers would seek to defend Baraitser’s application of Section 91, i.e., that he is too sick and prone to take his life. They would also argue why U.S. assurances given after her ruling (that he will not be thrown into harsh isolation in the U.S.) can not be trusted. The Supreme Court, if it decides to take the case, may or may not accept introduction of new evidence of the C.I.A.’s plot to kill or kidnap Assange, as the High Court allowed.

Assange is no stranger to the U.K. Supreme Court. He lost his appeal there in 2012 against extradition to Sweden, where he feared he’d then be sent onto the U.S. Instead he received political asylum from Ecuador and remained in its London embassy until he was dragged out by British police in April 2019 and thrown into Belmarsh, after which the extradition proceedings began.

3. The Case is Sent Back

Another option the High Court has is to “remit the matter to the magistrate’s court … with the opinion of the High Court, and may make such other order in relation to the matter … as it thinks fit,” according to the Senior Courts Act.

If the case goes back to magistrate’s court it would have in all likelihood be taken up again by Baraitser. But SHE was moved on in September from her post as a district judge to a new position as a circuit judge at South Eastern Circuit, based at Inner London Crown Court. The Queen appointed her on the advice of Lord Chancellor Robert Buckland QC MP and Burnett.

“If the High Court were to remit the case back to the lower court for a reconsideration and a new decision on a point that the trial judge (ie. Baraitser) had previously got wrong — something which by the way I think is distinctly possible — then the High Court would give the lower court guidance on how to make the decision correctly,” said CN legal analyst Alexander Mercouris.

“That leaves open the possibility that [the new district judge] could reconsider the decision, follow the High Court’s guidance, apply the test correctly, and still come to the same decision that Baraitser did before, which is that Assange should not be extradited to the U.S. because of the prison conditions there, and because of the danger to his life and health,” Mercouris said. However, a new district judge could come to a different conclusion, namely siding with the U.S.

Both sides can request to put new evidence before the reconvened magistrate’s court. The U.S. can ask the new district judge to allow it to present their assurances that Assange would not be put in Special Administrative Measures (SAMS) if he were to be extradited. And Assange’s team could seek to introduce details from a September Yahoo! News article about the C.I.A. plot to kill him. Both sides may want to put on new expert, medical witnesses to bolster their case. The district judge will have leeway to permit or reject any new evidence.

If the new judge should come to the same decision to discharge Assange, according to the Australian foreign ministry’s understanding, “then the appeal is taken to have been dismissed by the High Court.” But if the new judge comes to a different ruling, Assange’s discharge is “quashed.” Either side could then presumably take their case to the Supreme Court.

This raises the uncomfortable question of the timing of Baraitser’s removal from the case and Burnett’s involvement in it. The likelihood of a different outcome increases with Baraitser out of the way.

Regarding the option the High Court has to amend the lower court judgement, Mercouris said it would mean a specific point of law in Baraitser’s ruling could be corrected without affecting the High Court’s judgement to uphold it.

Another Consideration: ‘Improper Motivation’

There is another possibility, though most likely remote, that could tip the High Court ruling in Assange’s favor. The judges, perhaps taking into account the Yahoo! revelations, might find that the U.S. has not been properly motivated in pursuing Assange. The Australian Foreign Ministry’s key to its chart says that the judges must be satisfied that the extradition request was not “improperly motivated.”

“The Australian Foreign Ministry is absolutely right on the subject of ‘improper motivation’,” said Mercouris. “It is a fundamental principle that legal proceedings should not be used as an instrument to oppress another.”

If the High Court were “persuaded that the reason the U.S. wants to punish” Assange was simply because “as a journalist he had published information about the U.S. which was embarrassing, and that various charges under the Espionage Act were simply window dressing in order to achieve that result, then that would be oppressive, and an improper purpose, and the Court should refuse the extradition request,” Mercouris said.

He added:

“The High Court does have the power on appeal to overrule a lower court judge by itself finding that an extradition request is ‘improperly motivated’, and a possible pathway to achieving that in this case is by citing the Yahoo! report, which showed (1) the obsessive hostility to Assange of some elements of the U.S. government; (2) the extraordinary lengths to which they were prepared to go; and (3) the fact that they were prepared to go to these lengths in response to the Vault 7 revelations, which however are not a part of the extradition request. That fact shows that the true reason for the extradition request is to punish Assange because he has published embarrassing information, and not because he is really believed to have committed any crime.”

Mercouris said it is a hopeful sign for Assange that his lawyers were able to discuss the Yahoo! report at the hearing of the High Court. The court normally does not permit new evidence. Significantly, the U.S. lawyers did not contest it. In the September 2020 extradition hearing, Lewis had called talk of assassination plots against Assange “palpable nonsense.” At the High Court Lewis said nothing after hearing details of the Yahoo! story.

“There is some mystery here, and it could be that there has been a behind-the-scenes argument about the admissibility of this evidence — with a decision taken to allow it — which we do not know about,” Mercouris said.

The Threat of a New Extradition Request

US: "Even if we lose, we can start again with Mr. Assange and issue another extradition request" -James Lewis QC today at the UK High Court on behalf of the US Government

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) October 28, 2021

Toward the end of his rebuttal on the second day of the High Court hearing, Lewis made what seemed an ominous threat:

“I am stunned that Lewis actually said that if the current extradition request is refused, then the U.S. will simply make another one,” Mercouris said, who worked as a lawyer for 12 years at the Royal Courts of Justice. “I cannot imagine that the High Court was pleased by that comment. It sounds to me like an attempt to pressure the High Court, which judges would normally respond to badly.”

“If the U.S. strategy is to bring a fresh extradition request if the current one is refused, and to go on bringing extradition requests so as to keep Assange in prison indefinitely,” Mercouris said, “I would have thought that that was oppressive, with the High Court in that case obliged to dismiss all such new extradition requests, on the grounds that they were clearly ‘improperly motivated’, being intended to keep Assange in detention indefinitely even though he has been found guilty of no crime.”

But he hastened to add: “As was said during the hearing, there is nothing normal about this case.”

No comments:

Post a Comment