During the Covid-19 crisis, Jacobson v. Massachusetts became the fountainhead for scamdemic jurisprudence...

Authored by Bob Fielder: Stare Decisis is an old Latin phrase meaning “Let wrong decisions of the Court stand.” The term is more commonly spoken of today as the common-law doctrine of precedent.

Recent research on the part of constitutional law scholar Josh Blackman, his article “The Irrepressible Myth of Jacobson v. Massachusetts” demonstrated that over the course of a century, four prominent justices established a mythical narrative surrounding Jacobson v. Massachusetts that has obscured any historical view of this case as either a matter of law or fact. This myth has four levels:

- The first level was layered in Buck v. Bell (1927). Justice Oliver Wendall Holmes Jr. recast Jacobson’s limited holding to support forcible intrusions onto bodily autonomy. The Cambridge law did not involve forcible vaccination, but Holmes still used the case to uphold a compulsory sterilization regime.

- The second level was layered in 1963. In Sherbert v. Verner, Justice William J. Brennan transformed Jacobson, a substantive due process case, into a free exercise case. And he suggested that the usual First Amendment jurisprudence would not apply during public health crises.

- The third level was layered in 1973. In Roe v. Wade, Justice Harry Blackmun incorporated Jacobson into the Court’s modern substantive due process framework. Roe also inadvertently extended Jacobson yet further: during a health crisis, the state has additional powers to restrict abortions.

- The fourth layer is of recent vintage. In South Bay Pentecostal Church v. Newsom, Chief Justice John Roberts’ “superprecedent” suggested that Jacobson-level deference was warranted for all pandemic-related constitutional challenges.

This final layer of the myth, however, would be buried six months later in Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo. The per curiam decision followed traditional First Amendment doctrine, and did not rely on Jacobson. But Jacobson stands ready to open up an escape hatch from the Constitution during the next crisis. The Supreme Court should restore Jacobson to its original meaning, and permanently seal off that possibility.

Instead, Chief Justice Roberts wrote an influential concurring opinion. He favorably cited Jacobson, and wrote that, “Our Constitution principally entrusts ‘[t]he safety and the health of the people’ to the politically accountable officials of the States ‘to guard and protect.’” In short order, this concurrence became a “superprecedent.” Over the following six months, 140 cases cited the solo opinion, and more than 90 of which also cited Jacobson. It isn’t clear that the chief justice intended to adopt Jacobson’s constitutional analysis as a general rule to review pandemic measures

Jacobson v. Massachusetts was decided in February 1905, two months before the Supreme Court handed down Lochner v. New York. This period was known politically as the Progressive Era, and legally as the Lochner Era. Constitutional law was very different at the turn of the twentieth century. When reviewing decisions from this epoch, it is important to view them in the timeframe in which they were decided. It is anachronistic to view these cases through the lens of modernity. And it is problematic to graft these early cases onto the modern framework of constitutional law. Yet, courts and scholars routinely make these errors. Part I will provide a brief history of constitutional law from the Lochner era to the present. First, we will revisit the Fourteenth Amendment, as it was understood in 1905. At the time, there were no tiers of scrutiny, the Supreme Court did not distinguish between fundamental and non-fundamental rights, and the Bill of Rights had not yet been incorporated. So-called rational basis review was actually somewhat rigorous. Moreover, the Court treated economic property rights in the same fashion as personal liberty.

In 1905, the Supreme Court’s Fourteenth Amendment case law was primordial. The Privileges & Immunities Clause was an empty vessel. States were not bound by the Bill of Rights. And separate was equal. This jurisprudence was far removed from modern doctrine. The Supreme Court had not yet carved the tiers of scrutiny. There was no divide between rational basis scrutiny and strict scrutiny. Nor was there a sharp dichotomy between fundamental and non-fundamental rights. Yet, cases from the Progressive Era invoked concepts and terms that seem familiar to present-day students of constitutional law, but had very different meanings.

The Evolution to Modern Constitutional Law

Modern constitutional doctrine would begin, in earnest, three decades after Jacobson. The Supreme Court’s Progressive Era approach to the Fourteenth Amendment largely subsided during the New Deal. The Supreme Court’s present-day approach to the Due Process Clause springs from Footnote Four of United States v. Carolene Products. Justice Harlan F. Stone wrote the majority opinion. The first paragraph of Footnote Four stated that courts should not review with the presumption of constitutionality legislation that “appears on its face” to violate “a specific prohibition of the Constitution.” Specifically, that presumption of constitutionality is not warranted when a law runs afoul of rights protected by “the first ten Amendments.” For example, the Court should not use the presumption of constitutionality to review a law that violates the freedom of speech. Instead, the Court should invert the presumption of constitutionality to what may be called a presumption of liberty. With this approach, the government has the burden to justify why it is violating that enumerated right. The Court would later refer to this model as “strict scrutiny.” There was an unstated implication in the first paragraph of Footnote Four: nonfundamental rights that did not to violate “a specific prohibition of the Constitution” would be reviewed with the presumption of constitutionality. That is, most laws that burdened unenumerated rights would be reviewed with a deferential standard of review.

Jacobson and Lochner in 1905

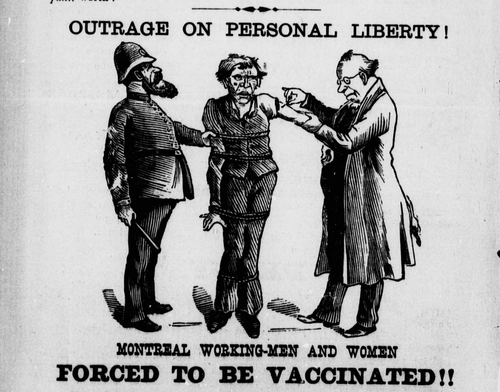

Around the turn of the twentieth century, states began to require people to be vaccinated against smallpox. And courts upheld these measures as constitutional exercises of the police power. In 1902, Massachusetts enacted such a law. Later that year, the city of Cambridge prosecuted Henning Jacobson for refusing to get vaccinated. Jacobson, a Lutheran Evangelical Minister, argued that the law violated the state and federal constitution. After a trial, Jacobson was convicted, and ordered to pay the maximum permissible fine: $5. The Massachusetts law did not allow the Commonwealth to forcibly vaccinate Jacobson. An unvaccinated person who paid the fine was free to spread smallpox, and still be fully compliant with the law.

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court upheld Jacobson’s conviction. It found that individual liberty could be restricted to promote the common welfare. On appeal, the United States Supreme Court agreed. Justice John Marshal Harlan wrote the majority opinion. So long as there was reasonable fit between the measure adopted, and the government’s interest was to promote public health, the law is valid. Still, Jacobson identified several limitation on its holding that are often disregarded in modern discourse.

We must juxtapose Jacobson with the infamous case of Lochner v. New York. The two cases, which were decided two months apart, are cut from the same constitutional cloth. Both of these cases should be viewed as byproducts of the early twentieth century jurisprudence. To understand Jacobson, we must understand Lochner.

A number of states put in place steep fines and penalties for non-compliance to vaccine requirements. Still, despite all of these draconian measures, the states did not purport to have the power to forcibly vaccinate people. By 1905, “not one of the states undertakes forcible vaccinations of its inhabitants, while the states of Utah and West Virginia expressly provide that no such compulsion shall be used.” Jacobson’s counsel, J.W. Pickering “contended that the rights of man under the constitution were such that the enforcement of the vaccination law took them away.”

Pfizer headquarters in New York City 🇺🇸 Protesters gather against mandatory vaccination for health workers pic.twitter.com/kmz4zRlRhx

— D1ll3yD1ll3y (@DilleyDilley8) November 14, 2021

Pickering added that vaccination “was a great menace to individual rights.” Moreover, “certain members of the medical fraternity did not believe in vaccination.” However, Judge McDaniel ruled that he could not pass on the constitutionality of the law in that court. Judge McDaniel ordered Jacobson to pay a fine of $5.

First, the Court placed the Massachusetts law in the broader context of public health laws. “Sometimes it is necessary,” Massachusetts Supreme Court Chief Justice Marcus Perrin Knowlton wrote, “that persons be held in quarantine.” Moreover, “Conscription may be authorized if the life of the nation is in peril.” Other state courts had upheld the power to require vaccinations “as a prerequisite to attendance at school.” From these precedents, the Court reasoned that the state has the power to mandate vaccinations for the entire populace. Here, the Court favorably cited decisions from “the highest courts of Georgia and North Carolina” which upheld “statutes substantially the same as the one now before us.” The Court rejected Jacobson’s claims based on the Due Process Clause. He stated that “[t]he rights of individuals must yield, if necessary, when the welfare of the whole community is at stake.” Chief Justice Knowlton cited several prominent U.S. Supreme Court decisions, including Powell v. Pennsylvania, Yick Wo v. Hopkins, and Mugler v. Kansas. These cases recognized that “if a statute purports to be enacted to promote the general welfare of the people, and is not at variance with any provision of the Constitution, the question whether it will be for the good of the community is a legislative, and not a judicial, question.” Third, the Court identified a limitation on its holding: the penalty was modest, and the state did not actually force people to get vaccinated. But the Court recognized the analysis would be different if the law did in fact force people to get vaccinated.

More than a century later, Justice Neil Gorsuch described the narrow scope of the Cambridge law: “individuals could accept the vaccine, pay the fine, or identify a basis for exemption.” He added that “the imposition on Mr. Jacobson’s claimed right to bodily integrity, thus, was avoidable and relatively modest.”

On appeal, Jacobson narrowed his arguments to five grounds. He limited his assignments of error to federal questions, and excluded all claims under the Massachusetts Constitution. First, Jacobson claimed that the law “was in derogation of the rights secured…by the preamble to the Constitution…and tends to subvert and defeat the purposes of said Constitution as there declared.” Second, he asserted that the law violated the Self Incrimination Clause, the Due Process Clause, and the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment. Third, Jacobson argued that the law violated Section One of the Fourteenth Amendment. Fourth, he claimed the law “was repugnant to the spirit of the Constitution of the United States.” Fifth, Jacobson alleged that the trial court erred by excluding his offers of proof about the vaccine’s harmfulness, which “tended to prove” that the law was “unconstitutional and void.”

The Supreme Court affirmed Jacobson’s conviction. Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote the majority opinion. Justices David Josiah Brewer and Rufus W. Peckham dissented without a written opinion. The Court rejected Jacobson’s first argument based on the preamble to the United States Constitution. Justice Harlan wrote that the preamble “has never been regarded as the source of any substantive power conferred on the government of the United States, or on any of its departments.”

To this day, courts cite Justice Harlan as the canonical statement for the relevance of the preamble. The Court did not address Jacobson’s second argument based on the Fifth Amendment. Justice Harlan quickly dispatched “without discussion” Jacobson’s fourth argument based on the “spirit” of the Constitution. He found there was “no need in this case to go beyond the plain, obvious meaning of the words in those provisions of the Constitution which, it is contended, must control our decision.” With respect to the fifth claim, the Court stated that the “mere rejection of defendant’s offers of proof does not strictly present a Federal question.”

The bulk of the opinion focused on the third assignment of error: Section One of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court rejected Jacobson’s argument that the Massachusetts law violated the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court also rejected Jacobson’s argument based on the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The remainder of Jacobson considered the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court posed the central question: “Is the statute, so construed, therefore, inconsistent with the liberty which the Constitution of the United States secures to every person against deprivation by the state?” The Court answered no. Justice Harlan’s analysis of the Due Process Clause had four primary parts.

First, the Court explained the relationship between individual liberty and the state’s police power. Justice Harlan wrote that the Constitution “does not import an absolute right in each person to be, at all times and in all circumstances, wholly freed from restraint.” All people can be subjected to “manifold restraints” to promote “the common good.”

Finally, the Court offered a two-part test to determine whether the Massachusetts law was valid. First, the Court asked “if a statute purporting to have been enacted to protect the public health, the public morals, or the public safety, has [a] real or substantial relation to those objects.” Second, the Court asks if the law “is, beyond all question, a plain, palpable invasion of rights secured by the fundamental law.” In either case, the Court has “the duty…to so adjudge, and thereby give effect to the Constitution.” The test resembles the sort of means-ends scrutiny that would become a staple of constitutional adjudication.

Justice Harlan’s opinion was broad. But the Court identified four limits, and implied a fifth constraint. First, structural constraints limit the state’s police powers. Second, the Court recognized that the statute cannot be enforced against a person for whom the vaccine would be particularly dangerous (“In perfect health and a fit subject of vaccination”). Third, Justice Harlan recognized that a vaccine mandate could not be enacted based on pretextual motivations: “if a statute purporting to have been enacted to protect the public health, the public morals, or the public safety, has no real or substantial relation to those objects,” then “it is the duty of the courts to so adjudge, and thereby give effect to the Constitution” which was enacted to “promote the common welfare.”

Fourth, the Court acknowledged that the government could not violate certain individual rights. Justice Harlan wrote, “There is, of course, a sphere within which the individual may assert the supremacy of his own will.” And if that sphere is encroached, people may “rightfully dispute the authority of…any free government existing under a written constitution, to interfere with the exercise of that will.” But that principle only went so far. Individual liberty “may at times, under the pressure of great dangers, be subjected to such restraint, to be enforced by reasonable regulations, as the safety of the general public may demand.” Justice Harlan drew the line at arbitrariness. The police power cannot be “exercised in particular circumstances and in reference to particular persons in such an arbitrary, unreasonable manner.”

Such an irrational requirement, Jacobson’s fifth constraint is implied, but is significant: the Court only upheld a small fine for going unvaccinated. The law did not actually require people to get vaccinated. Jacobson argued only that “his liberty is invaded when the state subjects him to fine or imprisonment for neglecting or refusing to submit to vaccination.” Having to pay the fine, Jacobson contended, was itself a violation of liberty, even if he was not forced to receive the vaccination. The case did not, and indeed could not, resolve the question of whether the state could force a person to undergo a medical procedure. Moreover, the fine was modest. Five dollars is roughly $150 in present-day value. (Justice Gorsuch rounded down to “about $140.”)

The narrow scope of Jacobson is linked to the narrow regime from Cambridge as applied to Jacobson’s specific dispute. The holding was expressly limited to this instance. Jacobson’s final sentence is worth repeating: “We now decide only that the statute covers the present case…” Over the next century, many judges would ignore this statement, and extend Jacobson to circumstances Justice Harlan could not have even fathomed.

Jacobson in the Roberts Court

On October 6, 2020, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo imposed new restrictions on public gatherings in houses of worship. These policies were challenged by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn, Agudath Israel of America, and other parties. The district court declined to enjoin Cuomo’s policy. It expressly recognized that Chief Justice Roberts “relied on Jacobson.” The court wrote, “in light of Jacobson and the Supreme Court’s recent decision in South Bay, it cannot be said that the Plaintiff has established a likelihood of success on the merits.” On November 9, the Second Circuit affirmed based on the South Bay concurrence. In dissent, Judge Park assailed Jacobson. He wrote, “Jacobson does not call for indefinite deference to the political branches exercising extraordinary emergency powers, nor does it counsel courts to abdicate their responsibility to review claims of constitutional violations.” That circuit court decision would be the last hurrah for the South Bay concurrence, and the fourth level of Jacobson’s myth.

The composition of the Supreme Court had changed since South Bay. Justice Ginsburg passed away, and was replaced by Justice Amy Coney Barrett. She took the judicial oath on October 27, 2020. And on November 12, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn sought an injunction from the new Roberts Court. Later that evening, Justice Alito delivered the keynote address at the Federalist Society National Lawyers Convention. He spoke at some length about COVID-19, religious liberty, and Jacobson:

So what are the courts doing in this crisis, when the constitutionality of COVID restrictions has been challenged in Court? The leading authority cited in their defense is a 1905 Supreme Court decision called Jacobson v. Massachusetts. The case concerned an outbreak of smallpox in Cambridge. And the Court upheld the constitutionality of an ordinance that required vaccinations to prevent the disease from spreading. Now I’m all in favor of preventing dangerous things from issuing out of Cambridge and infecting the rest of the country and the world. It would be good if what originates in Cambridge stayed in Cambridge. But to return to the serious point, it’s important to keep Jacobson in perspective. Its primary holding rejected a substantive due process challenge to a local measure that targeted a problem of limited scope. It did not involve sweeping restrictions imposed across the country for an extended period. And it does not mean that whenever there is an emergency, executive officials have unlimited unreviewable discretion.

On November 25, shortly before midnight, the Supreme Court decided Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo. The majority halted New York’s regulations. The per curiam opinion was unsigned. But, by process of elimination, we can infer that Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett were in the majority. Chief Justice Roberts and Justices Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan were in dissent. With Justice Barrett’s replacement of Ginsburg, the conservative court formed a new 5-4 majority.

The unsigned per curiam opinion was very short at less than 2,000 words. It did not cite Jacobson, or the Chief Justice’s South Bay concurrence. The mythical precedent of 1905 and the superprecedent of 2020 played no part in the Court’s decision. In Roman Catholic Diocese, the Court effectively repudiated the South Bay concurrence, and in the process, cast some doubt about the continued vitality of Jacobson—at least with respect to Free Exercise Clause cases. For our purposes, the most important aspects of the case were Justice Gorsuch’s concurrence and Chief Justice Roberts’ dissent. The two writings sparred over Jacobson.

No comments:

Post a Comment