For former residents of the Christian village of Iqrit, religious rituals bind them to a place from which the Jews newly established state of Israel had expelled them…

On Nov. 8, 1948, Jewish mercs had ordered Iqrit’s nearly 500 residents to leave; they were told they would be able to return, but during Christmas 1951 the Jews blew up their homes, leaving only the church standing…

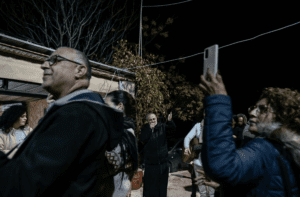

By Raja Abdulrahim: Amid the limestone ruins of homes in a village razed by Israeli forces long ago, a Christmas tree adorned with red and gold baubles went up on a recent evening, watched by a crowd of former residents and their descendants.

Shahnaz Doukhy, 44, her husband and two sons were among about 60 people who attended the tree lighting in the shadow of a roughly 200-year-old church, the only structure left standing after soldiers destroyed the Palestinian Christian village during Christmas 1951.

“It’s good for our kids to come and know that this is the land of their ancestors,” Ms. Doukhy said.

“And for them to continue with their kids,” added her husband, Haitham Doukhy, 53. “This is what connects us here, even if the village is no longer here.”

The couple put up a tree for the first time last year, hoping to start a tradition for the families of people expelled from Iqrit decades ago, whose attempts to return to live there have been repeatedly blocked by the Israeli government and military.

They come to the church for monthly Mass, Easter, weddings and baptisms, driving from miles away across northern Israel, past Jewish towns that did not exist when Iqrit was a small but thriving village.

“We observe the main stations of our life — birth, marriage and death,” said Shadia Sbeit, 50, whose two children were baptized in the church. “What we miss is the years between.”

On Dec. 26, the church will hold a Christmas Mass — an observance mixed with joy and bitterness given Iqrit’s history.

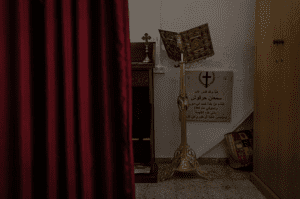

The church, at the top of a hill overlooking agricultural lands and the village cemetery, was founded in the early 1800s by a priest from Syria, who is buried inside. Small imprints of crosses and crescents line the top of its bricks, a nod by its Muslim architect to the closeness of Islam and Christianity.

Iqrit’s faithful say the church is about more than just religion.

It represents feeling at home and a small salve for the pain of displacement, bringing them closer to the stories passed on by their grandparents.

Hundreds of depopulated and destroyed Palestinian villages in present-day Israel share a fate similar to Iqrit’s — left behind as some 700,000 Palestinians were expelled or fled their homes in 1948 during the war surrounding Israel’s establishment as a state. Palestinians call the mass expulsions the Nakba, or catastrophe.

On Nov. 8, 1948, the Israeli military ordered Iqrit’s nearly 500 residents to leave so it could create a military buffer zone near the border with Lebanon.

They were told that they could return in two weeks, according to court documents and residents.

But their pleas to return were rejected by the regional military governor, government records show.

In 1951, they appealed to Israel’s Supreme Court.

That July, the court ruled that they were “permitted to settle the village of Iqrit.” But the military blocked their return.

Then, during Christmas, the army blew up their homes, leaving only the church standing, according to a telegram sent to an Israeli state lawyer by Iqrit residents days later.

In 2003, the residents appealed again to the court. This time, it ruled against them.

Israel maintained that it could not allow them to return “due to the heavy consequences such a step would have on the political level,” according to the court decision.

“The precedent of the resettlement of the displaced of the village will be used for propaganda and politics by the Palestinian Authority,” it added, citing the state’s argument and referring to the body that administers parts of the Israeli-occupied West Bank.

The right of return for the hundreds of thousands of displaced Palestinians and millions of their descendants has long been a key demand during Palestinian-Israeli peace negotiations, but one that Israel has largely rejected.

Still, many hope to return to their ancestral villages.

Graffiti around Iqrit give expression to that dream. “I will not remain a refugee. We will return,” reads a message on a storage shed.

In the late 1960s, former residents and their families began visiting the village after Israeli military rule ended for Palestinian citizens of Israel and they were allowed to move around the country more freely.

They said they found the church in disrepair and overrun by animals. They cleaned and renovated it — adding new tiles and pews and covering the walls with stucco.

Above the altar are portraits of Jesus, the Twelve Apostles and Mary, preserved by residents of a nearby Palestinian Christian village and handed back when people began returning to the church.

“They are witnesses to the history,” Father Soheel Khoury, who leads the Iqrit congregation, said, looking at the medieval-style paintings.

On a wall, a black-and-white photograph shows the village before 1948, with dozens of homes along the hillsides.

After the tree lighting, Khalil Kasis, 45, stood with his two children and pointed toward the valley below in the direction of a cluster of trees and the cemetery.

“We used to come here all the time and have barbecues there,” he said.

“You used to live here?” Amir, 13, his son, asked excitedly.

“No, no,” his father said. “Our family house was on the other side of the church, but it was destroyed a long time ago.”

He and his wife try to bring their children to Iqrit a few times a year, he said.

“We try to show the kids …, ” he began but trailed off, “we try to impart to them the cause.”

Nearby along the church wall, other children took turns grabbing the rope and ringing the church bell.

Naheel Toumie, 59, who was trying to coax Maria, her reluctant 2-year-old granddaughter, to take a photograph with the tree, said she helped organize summer camps there. Doing so for the descendants of former villagers was important, “so they can know who they are and where they’re from,” she said.

They begin by taking the children to the cemetery and telling them the story of the village and those who lived in it.

“It seems like we’re only going to return as dead bodies,” she said. “We’re not allowed to return while we’re alive.”

Some did try to return in the 1970s, when a few former residents in their 60s and 70s moved into the church as a form of protest.

Ilyas Dawood was among them.

For four years, starting in 1973, he lived in the church with other village elders, with their children bringing them food and water. In 1977, at 71, he died of a heart attack at the church doorstep.

Near the cemetery entrance a large plaque honors him and the others who lived in the church and were buried there.

“This monument was erected in memory of our fathers and mothers who clung to Iqrit’s church in the hope of returning alive,” it reads. “They moved into the afterlife as refugees in their homeland.”

They had yearned to rebuild family homes and live among the rolling hills where they spent childhoods picking laurel, thyme and olives. Instead, they returned to small limestone family tombs decorated with crosses, rosaries and pots of fake flowers.

No comments:

Post a Comment