In 2021/22 there were 4.7 million people, or 7% of the UK population, in food poverty, including 12% of children.

In 2022/23, the Trussell Trust, a charity and network of foodbanks, supplied the highest recorded number of three-day emergency food parcels.

This briefing provides statistics on food poverty in the UK, including food banks and free school meals.

There is no widely accepted definition of ‘food poverty’. However, a household can broadly be defined as experiencing food poverty or ‘household food insecurity’ if they cannot (or are uncertain about whether they can) acquire “an adequate quality or sufficient quantity of food in socially acceptable ways”.

According to the Department for Work and Pensions’ (DWP) Households Below Average Income survey, in 2021/22, 4.7 million people (7%) in the UK were in food insecure households. Among the 11.0 million people found to be in relative poverty, 15% were in food insecure households, including 21% of children. People in relative poverty live in a household with income less than 60% of the contemporary median income.

Food bank use in the UK

Food banks are run by charities and are intended as a temporary provision to supply emergency food.

The DWP published statistics on food bank use for the first time in March 2023. In 2021/22, 2.1 million people in the UK lived in household which had used a food bank in the previous 12 months, a rate of 3%. This includes 6% of children, 3% of working-age adults, and around 0% of pensioners.

In 2022/23, the Trussell Trust supplied 2.99 million three-day emergency food parcels.

How the rising cost of living affects food insecurity

Food prices have been rising since the second half of 2021. Food and non-alcoholic drink prices were 19.1% higher in the 12 months to March 2023, the highest since 1977. In July 2023, food inflation was 14.8%.

In July and August 2023, 56% of adults in Great Britain reported an increase in their cost of living compared with the month before according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Of these, 97% saw the price of their food shopping go up, and 47% had started spending less on essentials including food.

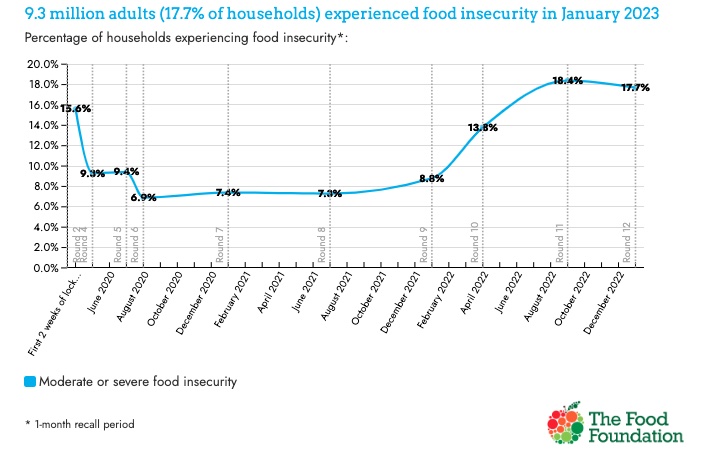

The rising cost of living seems to be increasing household food insecurity. A YouGov survey by the Food Foundation, a food poverty charity, found that in June 2023, 17.0% of households in the UK were ‘food insecure’ (ate less or went a day without eating because they couldn’t access or afford food), up from 8.8% in January 2022 and 7.4% in January 2021.

More than 760,000 people used a Trussell Trust food bank for the first time in 2022/23, a 38% increase from 2021/22.

Free school meals in England

In England, free school meals (FSM) are a statutory entitlement available to eligible pupils. Local authorities are responsible for providing FSM.

In January 2023, there were around 2.0 million pupils known to be eligible for FSM, representing 23.8% of state funded pupils. This eligibility rate has increased particularly sharply in the last few years (since 2018) and is the highest rate recorded since the current time series began in 2006.

This increase could be driven by many factors including macro-economic conditions, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the continued effect of the transitional protections during the rollout of Universal Credit.

Free school meals and educational attainment

On average, pupils eligible for free school meals achieve lower GCSE attainment than other pupils. This is based on achieving a “standard pass” in English and maths GCSE. Government statistics show that in 2022, 47% of pupils eligible for FSM achieved a standard pass in both English and Maths GCSE compared to 75% of pupils not eligible. This was an attainment gap of around 28 percentage points.

_________________

The UK’s rate of food poverty is among the worst in Europe. As the cost of living crisis makes it harder for people to afford to eat, we explain what you need to know about the country’s growing hunger crisis

By Isabella McRae, Hannah Westwater: The cost of living crisis is exposing the severity of food poverty in the UK. Millions are being pushed below the breadline as food prices soar, with many struggling to feed themselves and their families.

Food prices increased by 19.1 per cent in the 12 months to March 2023, the sharpest jump since August 1977.

The Trussell Trust saw record numbers of people seeking help between April 2022 and March 2023, with more than 760,000 people forced to turn to the charity’s food banks for the first time. That is more than the population of Sheffield.

Helen Barnard, the director of policy at the Trussell Trust, told the Big Issue: “It makes me very sad. It also makes me angry that as a society we’re allowing more and more people to be put in a position where they’ve got no option but to turn to charities for the real basics of life.”

These figures represent just a fraction of the UK’s charitable food aid network. Over 89 per cent of independent food banks reported increased need for their services in December 2022 compared with December 2021.

And many people who cannot afford food are suffering in silence.

This is what you need to know about the causes of food poverty in the UK and campaigners’ fight to end it as the cost of living crisis spirals.

What is food poverty?

People living in food poverty either don’t have enough money to buy sufficient nutritious food, struggle to get it because it is not easily accessible in their community, or both. It can be a long-term issue in someone’s life or can affect someone for a shorter period of time because of a sudden change in their personal circumstances.

Food insecurity leaves many people reliant on emergency parcels from food banks. For children living in food poverty, a free school meal could be the only guaranteed hot food they eat in a day. Families can sometimes be pushed into crisis during the school holidays because they cannot afford to pay for the food their children would have received during term time.

- UK poverty: the facts, figures and effects in a cost of living crisis

- Child poverty in the UK: The definitions, details, causes, and consequences

- UK fuel poverty in 2022: Causes, statistics and solutions

That can also mean parents eat less or skip meals entirely to make sure there is enough for their children to eat. Some people find they can only afford unhealthy food lacking nutrition, widening health inequalities between wealthy and disadvantaged people in the UK.

Researchers at the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising (IPA) found that “people are having to buy what they can afford rather than having the luxury of choice” in the cost of living crisis – often, that means opting for the unhealthy option. Other people don’t live in a home with facilities for cooking or storing meals.

The UK also has a problem with so-called “food deserts”, areas where people have little access to big supermarkets. Many of these areas are dotted with smaller convenience stores – which are demonstrably more expensive and less likely to stock fresh, healthy supplies – and force people who can’t afford private transport to go without the healthy food they need.

How many people are in food poverty in the UK?

The UK’s food poverty rate is among the highest in Europe. Despite being the sixth richest country in the world, millions are struggling to access the food they need.

According to the latest government statistics, 4.2 million people (6 per cent) were living in food poverty in 2020 to 2021. It includes nearly one in 10 children, around 9 per cent.

With the cost of living crisis, the situation is only getting worse. A total of 9.3 million adults experienced food insecurity in January 2023, the Food Foundation reports. That is around 17.7 per cent of all households.

A total of 3.2 million adults (6.1 per cent of households) reported not eating for a whole day because they couldn’t afford or access food.

It is particularly hitting low-income families. Over half (53.8 per cent) of universal credit claimants faced food poverty in January.

Key workers are more likely to be experiencing food insecurity than the average population. Around one in five teachers (21 per cent) and one in four NHS workers (24.9 per cent) are experiencing food poverty.

How many people are using food banks in the UK?

As a result of the cost of living crisis, Brits’ reliance on food banks is increasing rapidly. More than 760,000 people turned to Trussell Trust food banks for the first time between April 2022 and March 2023.

Over three million food parcels were given out during this 12 month period – more than ever before. More than a million of these parcels went to children.

This represents just a fraction of the national picture. According to the Independent Food Aid Network, over 89 per cent of member organisations reported increased need for their services comparing December 2021 with December 2022.

Kathy Bland of the Leominster Food Bank in Herefordshire said: “We are consulting with our volunteers and clients to plan how to cope with increasing numbers and what we might need to do differently. We had hoped to become a smaller organisation post-Covid. We will need to become a much larger and more resilient organisation to meet the increased level of need. It should be the welfare system that supports people properly. Not us.”

Around 80 per cent of groups reported helping both people who had not previously accessed support and those needing regular food aid. And from September to November 2022, over two thirds of organisations had experienced supply issues.

Half of contributing organisations said if demand increased, they would have to ration supplies or turn people away.

Jen Coleman of Black Country Foodbank in Dudley said: “Staff and volunteers are physically and mentally tired and we worry especially that our food bank volunteers will not be able to continue at this rate for long.”

Judith Vickers, at Lifeshare in Manchester City, added: “Staff are reporting burnout, heavy caseloads, and constant stream of new referrals. We are coping, but the level of demand is relentless. Volunteers often feel that we can’t do enough for people. But with the demand so high, our best option is to continue to support clients as best we can within the guidelines of our service.”

The number of families struggling to afford food is likely higher than food bank figures would suggest, as some people report the stigma and shame around poverty being enough to stop them seeking help to eat.

How many children are eligible for free school meals?

Just under 1.9 million children are eligible for free school meals in England, according to the latest government figures. This is 22.5 per cent of state school pupils. It is an increase of nearly 160,000 pupils since January 2021, when 1.74 million (20.8 per cent) of students were eligible for free school meals.

Charities including the Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) have found more than 800,000 children living in poverty are not eligible for free school meals.

Your support changes lives. Find out how you can help us help more people by signing up for a subscription

What causes food poverty?

Most people who fall into food poverty struggle because their income is too low or unreliable. This can be caused by low wages, a patchy social security system and benefit sanctions, which make it difficult to cover rent, fuel and food costs.

More than three quarters of people (76 per cent) responding to a Food Standards Agency survey said that rising food prices were a “major future concern” for them. Individuals living with long-term health conditions, women, and people from Black, Asian, and minority ethnic backgrounds were more likely to express anxiety about the cost of food, the study found.

Food poverty can also be a result of living costs which are rising much faster than average pay does, which is why the Living Wage Foundation encourages employers to voluntarily commit to paying the “real living wage” – calculated according to the real cost of living.

One in five people referred to a food bank in the Trussell Trust network are from working households, according to the charity. Food banks are supporting an increasing number of people who are working but still can’t afford the essentials – which is leading to food banks having to change their opening times so people can pick up food outside of working hours.

Mounting debt can trap people in poverty and force them to rely on food banks, while disabilities and mental health problems make it harder for people to afford the food they need.

Why is food poverty increasing in the UK?

Soaring prices are affecting household budgets, which means families are increasingly experiencing food insecurity. Food and non-alcoholic beverage prices rose by 19.1 per cent in the 12 months to March 2023. The costs of staple items like bread, cheese and milk have skyrocketed.

Prices are rising even faster for poorer households. This is because the costs of essentials are soaring at higher rates, and low-income families typically spend a greater proportion of their income on these items.

Experts also point to local authority budget cuts and a failing welfare safety net as a major driver of food bank use, with the five-week wait for universal credit, the two-child limit and the benefit cap among some of the policies trapping people in poverty.

And the no recourse to public funds policy, which stops people accessing benefits or any help from the state due to their immigration status, is also at the root of the crisis for many people in the UK.

Mary McGinley, at Helensburgh Foodbank in Argyll and Bute, says: “There is a concern that social services and statutory agencies expect the food bank volunteers to fill the gap that they themselves can’t fill. It is easy to signpost individuals to the food bank rather than to manage clients through a benefits review or provide access to an emergency welfare payment or energy top-up.

“We expect to be even busier, but it will be difficult to cope with this increase in demand. The UK government seems to think that if we just wait for inflation to come down all will be well. It wasn’t ‘well’ before the increase in inflation. Real action is required.”

Who is most affected by food poverty?

People who are already struggling are most likely to be affected by food poverty. Over half of households on universal credit experienced food insecurity in January 2023, according to the Food Foundation.

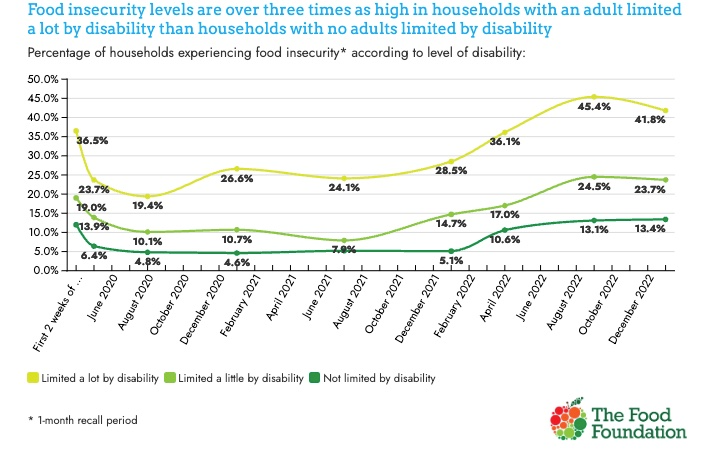

There has been a widening of inequalities experienced by people with disabilities. Food insecurity levels are more than three times higher in households with an adult severely limited by disability than households with no disabled adults.

Non-white ethnic groups are more likely to be food insecure than white ethnic groups (27.9 per cent in comparison to 18.2 per cent), according to the latest Food Foundation statistics.

Where is food poverty worst?

According to the Food Foundation, food poverty is worst in the north east of the country – where 27.8 per cent of residents faced difficulties affording food in September 2022. Scotland also has high levels of food poverty at 24.2 per cent, while Northern Ireland reports levels at 22.4 per cent.

The TUC found one in seven people across the UK (14 per cent) were skipping meals or going without food in October because they couldn’t afford the essentials. And over two-fifths (44 per cent) of Brits are having to cut back on food spending. But it’s worse in some areas of the country.

In Birmingham Ladywood, well over one in four (29 per cent) of people are skipping or going without food, according to the TUC. That’s followed by Dundee West (27 per cent), Glasgow (24 per cent) and Rhondda (24 per cent).

In Bootle, Birmingham Ladywood and Liverpool Walton, six in 10 constituents are cutting back on food spending. But in wealthier constituencies like Richmond Park and Chelsea and Fulham, it’s still affecting three in 10 local residents.

People in London areas including Croydon and Southwark as well as cities in the north of England like Liverpool, Manchester and Newcastle have high rates of food poverty.

Demand for free school meals is highest in the north-east, where around 29.1 per cent of children currently qualify, compared to just 17.6 per cent in the South East.

How can we end food poverty?

Charities and experts have called on the government to do more to help people through the cost of living crisis. This means targeted support for people living in poverty through increases to universal credit and minimum wage, an expansion of the free school meals scheme and a freeze on rents.

Campaigners have called on the government to expand its free school meals scheme, to ensure that children are guaranteed a full hot meal every day.

Jo Ralling, of the Food Foundation, told the Big Issue: “We have over 800,000 children living in poverty who currently do not qualify for a free school meal and the government urgently needs to extend the scheme. We know that well nourished children have better attendance, increased concentration which leads to better academic results.”

Food charities including Chefs in Schools, the Food Foundation, and celebrity chefs like Jamie Oliver and Tom Kerridge, launched a campaign ‘Feed the Future’ last year calling on the government to urgently extend free school meals eligibility to all children from families in receipt of universal credit.

Research conducted as part of the campaign revealed expanding the free school meals scheme could generate billions for the economy.

More than 90 charities and organisations are currently calling on political leaders to guarantee that people will be able to afford the basics they need to live.

“We must remind political leaders that, whether they like it or not, this is driving millions of people into hardship and it is not a problem that will go away without bold and concerted action,” Katie Schmuecker, the principal policy adviser at JRF, said.

“It is time to build a system that is needs-tested – where the support people get is linked to the actual costs of essentials to meet basic needs rather than the baseless system people have to suffer now.”

Sabine Goodwin, coordinator at the Independent Food Aid Network, added: “Guaranteeing people can afford essential costs shouldn’t be in question. We need a social security system that’s fit for purpose and ensures people can live and thrive whether they can or can’t work.”

No comments:

Post a Comment